Practicing Safe Philosophy

In secular colleges and universities, there are analogous perilous pursuits. Well, we know that in the United States there was a Red Scare, with two periods: the First Red Scare (1918-1920), followed by a Second Red Scare (1947-1957), also know as McCartyism. These Red Scares led to loss of jobs, imprisonment, and deportations.

In 1967, Noam Chomsky published an article, “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,”, which is “to speak the truth and expose lies” of governments.

But for a political philosopher there is a more fundamental question: Is any form of a centralized government, i.e., a State, legitimate?

A political philosopher can evade this question by simply doing a sort of literary analysis of some historical political philosopher, and refrain from giving their own considered answer. As an example of this evasion, I came across a video by Tamar Gendler, Professor of Philosophy and Cognitive Science, and Chair of the Philosophy Department, Yale University, whose video exemplifies this safe academic approach. Her lecture is titled: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Politics.

Both Rawls and Nozick assume the kind of liberal democracy we have in the United States, and their disagreement is over policies of such a government. Rawls is for a welfare state. Nozick is against a welfare state. But the fundamental question which was raised by Rousseau as to the legitimacy of a State is side-stepped.

Instead of beginning with Rawls or Nozick, I think it is more appropriate (though not as safe) to begin with Robert Paul Wolff’s In Defense of Anarchism (1970),

Here is a 2008 audio interview with Wolff on anarchism: Doing without a ruler: in defense of anarchism

Political Correctness in Academia

I became aware of this censorship in academia by sheer accident in 1973. I was heading towards Key West in my VW camping bus, and on the way I stopped by the University of Florida where I came across a news item that a philosopher was in court fighting his firing. I had forgotten his name, but I do remember that he was a Marxist who spoke his mind in an unvarnished fashion. I stayed to listen to the testimony of the president and others. But I did not stay to find out the outcome of these hearings. But searching the internet, I have found out that the philosopher was Kenneth A. Megill, who appealed a denial of tenure by President Stephen C. O’Connell. I found the following court ruling: Dr. Kenneth A. MEGILL, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. BOARD OF REGENTS OF the STATE OF FLORIDA et al., Defendants-Appellees.

I remember other such cases. The one that sticks in my mind was the dismissal of Saul Kripke. At the time I heard of this, I was — let us say — bewildered: Saul Kripke??? Again, scouring the internet, I found this informative piece: Israel Shenker, “Rockefeller University Hit by Storm Over Tenure,” Sept. 26, 1976. Reading the piece, I discover that a whole group of other eminent philosophers had to find employment elsewhere.

Other cases of professors being fired — the euphemism is non-reappointment — or denied tenure which come to mind, are that of Howard Zinn who was dismissed from Spelman College in 1963 for supporting student protests as an act of insubordination.

The case of Norman Finkelstein was especially disconcerting to me, and I wrote a big analytical piece about it: Norman Finkelstein, DePaul, and U.S. Academia: Reductio Ad Absurdum of Centralized Universities, July 23, 2007.

There is a short clip of me here, identified as Philosophy Teacher, Wright College, Chicago, offering my two bits :

Professor Finkelstein’s DePaul Farwell, Sept. 5. 2007:

Below is a full-documentary about Norman Finkelstein:

American Radical: The trials of Norman Finkelstein [2009]

Ward Churchill, a tenured professor, was fired from the University of Colorado in 2007 on alleged plagiarism charges but really for claiming in an article and a book that the 9/11/2001 attack against the World Trade Center was — to use Chalmers Johnson’s CIA word — a “blowback” for the U.S. policies in the Middle East. Churchill took the wrongfull dismissal case to a court, and won; but was not reinstated. The controversial article was “Some People Push Back: On the Justice of Roosting Chickens,”, Sept. 12, 2001, and the book was On the Justice of Roosting Chickens: Reflections on the Consequences of U.S. Imperial Arrogance and Criminality, 2003.

Below is Megyn Kelly’s commentary and interview with Ward Churchill in 2014.

There is also the case of David Graeber whose contract was not renewed at Yale. Below is a link to an interview with Graeber about this affair.

Joshua Frank, “David Graeber is Gone: Revisiting His Wrongful Termination from Yale,” Counterpunch, September 4, 2020.

The whole issue of censorship in America has recently been put on film: No Safe Spaces

Bertrand Russell’s bullshit interpretation of Jean Jacques Rousseau

Chapter 19 of his History is about Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) who is known primarily for his essays, as collected in , The Social Contract and Discourses, translated with an introduction by G.D.H. Cole, 1913. [(In my American edition of 1950, there is an 1931 entry in the Bibliography. ]

Some regard Rousseau as the greatest political philosopher. Here are two such opinions;

“. . . Jean-Jacques Rousseau is the greatest political philosopher who has ever lived. His claim to immortality rests upon one short book, Of the Social Contract . . .” Robert Paul Wolff, About Philosophy 9th ed. (2006), p. 318.

G. D. H, Cole (1889-1959), in his clear and insightful introduction to Rousseau’s essays, writes: “. . . the Social Contract itself is by far the best of all textbooks of political philosophy.” (p. l)

Bertrand Russell, on the other hand, describes Rousseau in the most disparaging ways. Let me cite the most outrageous of his claims:

1. “. . . the inventor of the political philosophy of pseudo-democratic dictatorship as opposed to traditional absolute monarchies.”

2. “Hitler is an outcome of Rousseau; Roosevelt and Churchill of Locke.”

3. “Rousseau forgets his romanticism and speaks like a sophistical policeman. Hegel, who owed much to Rousseau, adopted his misuse of the word “freedom,” and defined it as the right to obey the police, or something not very different.”

4. “Its doctrines, though they pay lip-service to democracy, tend to the justification of the totalitarian State.”

5. The final paragraph of Russell’s chapter on Rousseau is this:

“The Social Contract became the Bible of most of the leaders in the French Revolution, but no doubt, as is the fate of Bibles, it was not carefully read and was still less understood by many of its disciples. It introduced the habit of metaphysical abstractions among the theorists of democracy, and by its doctrine of the general will it made possible the mystic identification of a leader with its people, which has no need of confirmation by so mundane an application as the ballot-box, Much of its philosophy could be appropriated by Hegel. [Hegel selects for special praise the distinction between the general will and the will of all. He says: “Rousseau would have made a sounder contribution towards a theory of the State, if he had always kept the distinction in mind.” (Logic, Sec. 163).] in his defense of the Prussian autocracy. Its first-fruit in practice was the reign of Robespierre, the dictatorship of Russia and Germany (especially the latter) are in part an outcome of Rousseau’s teaching. What further triumphs the future has to offer to his ghost I do not venture to predict.”

I find all these claims bizarre — a complete misunderstanding of Rousseau.

As an immediate antidote to this misreading, I recommend the introduction to the essays by G.D.H. Cole, and an essay which Cole recommended as a historical summary of the social contract tradition by D.G. Ritchie, “Chapter 7. Contributions to the History of the Social Contract Theory,” (pp. 196-226) in Darwin and Hegel with Other Philosophical Studies (1893)

Although in my opinion Russell totally misunderstood Rousseau’s Social Contract, for the sake of what I am about to say, let us assume (pretend) that Russell’s interpretation of Rousseau is correct. Let us assume (pretend) that Rousseau was espousing a dictatorship of a leader. How does such an alleged espousal lead to, cause, influence, or inspire Hitler?

To make such a claim at least plausible would require, I think, the following presuppositions:

1. Intellectuals have an influence on the general public, or

2. Intellectuals have an influence on politicians, or

3. Hitler was influenced by Rousseau.

My general view is that intellectuals are taken notice of by mostly other intellectuals, and hardly at all by the general public or by politicians. This is to say that intellectuals have almost no effect on politics.

The exceptions are — to speak sarcastically — philosopher kings, i.e., politicians who happen to be intellectuals. I am thinking of such figures as Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, Woodrow Wilson (in the United States); Thomas Masaryk in Czechoslovakia; Lenin and Trotsky in Russia; and such.

Was Hitler an intellectual? And if he read Rousseau, what did he get from him? How in the world does one support the thesis that Hitler is an outcome of Rousseau?

Looking on the Internet whether anyone else commented on Russell’s view of Rousseau, I came across the following interesting piece: Thomas Riggins, “Russell, Rousseau, And Rationality: A Marxist Critique,” Countercurrents.org, June 30, 2007.

What is Double-Speak?

Criticism of Karl Popper in Broad Strokes

He is against nationalism. But the word “nationalism” is itself not clear, and he does not clarify it, and uses it as synonymous with an anthropological description of primitive (indigenous) tribes. And he is correct to think of primitive tribes as closed societies, meaning that there is total conformity as to mores and beliefs. And this is well illustrated by the example of Socrates who was killed both for corrupting the youth and for impiety. But he is wrong about modern nation-states. Many tolerated both religious and political criticism.

My understanding of “nationalism” (and this may very well be idiosyncratic to me), is that people speaking a common language want to be autonomous. As far as I am concerned this does not require having an independent State — an anarchistic federation of communities will do; though historically people with a common language have formed States. And it is totally puzzling to me why Popper failed to acknowledge this.

His general objections to social and territorial groupings of people is that these matters are vague with borderline cases. This is true, and there is nothing “natural” about this (as he points out); it is conventional. His objection to a demarcation of people by language is that there are dialects. But with the writing of dictionaries there is a sort of crystallization of languages.

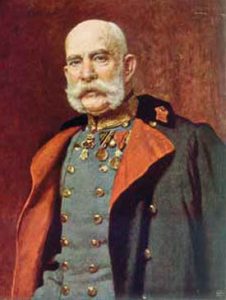

I think that Popper, despite acknowledging that States were formed through conquest, thought that they were necessary, and would have arisen nonetheless for other reasons. And I do not see any criticism in Popper of imperial States, including the Austro-Hungarian Empire into which he was born. He would, I think, accept a constitutional monarchy, as long as there existed a mechanism for removing a tyrant from office.

He believed that the function of a State and even of some international institution, like a League of Nations, was to protect individuals — even within States. His view of the role of government in States is made abundantly clear in his discussion and defense of the position of the ancient Sophist, Lycophron (Open Society 1: pp. 114-17).

I think he lamented the disappearance of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He simply thought that Franz Joseph, Emperor of Austria, did not do a good enough job of protecting minorities in his empire.

Karl Popper on the Origin of the State

I have also greatly admired his scholarship. As an example, I reproduce his findings on the origin of the State through conquest — a position with which I agree. However, a fundamental disagreement that I have with Popper is whether the State can be dispensed with. He thinks the State is indispensable and can be justified. I disagree on both counts. But I leave this issue for another occasion.

Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, Chapter 4: footnote 43:

Plato’s remarkable theory that the state, i.e. centralized and organized political power, originates through a conquest (the subjugation of a sedentary agricultural population by nomads or hunters) was, as far as I know, first re-discovered (if we discount some remarks by Machiavelli) by Hume in his criticism of the historical version of the contract theory (cp. his Political Discourses, 1752, the chapter Of the Original Contract): — ‘Almost all the governments’, Hume writes, ‘which exist at present, or of which there remains any record in history, have been founded originally on usurpation or conquest, or both . . .’ The theory was next revived by Renan, in What is a Nation? (1882), and by Nietzsche in his Genealogy of Morals (1887); see the third German edition of 1894, p. 98. The latter writes of the origin of the ‘state’: ‘Some horde of blonde beasts, a conquering master race with a war-like organization . . lay their terrifying paws heavily upon a population which is perhaps immensely superior in — numbers. . . This is the way in which the “state” originates upon earth; I think that the sentimentality which lets it originate with a “contract”, is dead.’ This theory appeals to Nietzsche because he likes these blonde beasts. But it has been also more recently proffered by F. Oppenheimer (The State, transl. Gitterman, 1914, p. 68); by a Marxist, K. Kautsky (in his book on The Materialist Interpretation of History); and by W. G. Macleod (The Origin and History of Politics, 1931). I think it very likely that something of the kind described by Plato, Hume, and Nietzsche has happened in many, if not in all, cases. I am speaking only about ‘states’ in the sense of organized and even centralized political power.

I may mention that Toynbee has a very different theory. But before discussing it, I wish first to make it clear that from the anti-historicist point of view, the question is of no great importance. It is perhaps interesting in itself to consider how ‘states’ originated, but it has no bearing whatever upon the sociology of states, as I understand it, i.e. upon political technology (see chapters 3, 9, and 25).

Toynbee’s theory does not confine itself to ‘states’ in the sense of organized and centralized political power. He discusses, rather, the ‘origin of civilizations’. But here begins the difficulty ; for what he calls ‘civilizations’ are, in part, ‘states’ (as here described), in part societies like that of the Eskimos, which are not states; and if it is questionable whether ‘states’ originate according to one single scheme, then it must be even more doubtful when we consider a class of such diverse social phenomena as the early Egyptian and Mesopotamian states and their institutions and technique on the one side, and the Eskimo way of living on the other.

But we may concentrate on Toynbee’s description (A Study of History, vol. I, 305 ff.) of the origin of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian ‘civilizations’. His theory is that the challenge of a difficult jungle environment rouses a response from ingenious and enterprising leaders; they lead their followers into the valleys which they begin to cultivate, and found states. This (Hegelian and Bergsonian) theory of the creative genius as a cultural and political leader appears to me most romantic. If we take Egypt, then we must look, first of all, for the origin of the caste system. This, I believe, is most likely the result of conquests, just as in India where every new wave of conquerors imposed a new caste upon the old ones. But there are other arguments. Toynbee himself favours a theory which is probably correct, namely, that animal breeding and especially animal training is a later, a more advanced and a more difficult stage of development than mere agriculture, and that this advanced step is taken by the nomads of the steppe. But in Egypt we find both agriculture and animal breeding, and the same holds for most of the early ‘states’ (though not for all the American ones, I gather). This seems to be a sign that these states contain a nomadic element; and it seems only natural to venture the hypothesis that this element is due to nomad invaders imposing their rule, a caste rule, upon the original agricultural population. This theory disagrees with Toynbee’s contention (op. cit. III, 23 f.) that nomad-built states usually wither away very quickly. But the fact that many of the early caste states go in for the breeding of animals has to be explained somehow.

The idea that nomads or even hunters constituted the original upper class is corroborated by the age-old and still surviving upper-class traditions according to which war, hunting, and horses, are the symbols of the leisured classes; a tradition which formed the basis of Aristotle’s ethics and politics, and is still alive, as Veblen (The Theory of the Leisure Class) and Toynbee himself have shown; and to these traditions we can perhaps add the animal breeder’s belief in racialism, and especially in the racial superiority of the upper class. The latter belief which is so pronounced in caste states and in Plato and in Aristotle is held by Toynbee to be ‘one of the . . sins of our . . modern age’ and ‘something alien from the Hellenic genius’ (op. cit., III, 93). But although many Greeks may have developed beyond racialism, it seems likely that Plato’s and Aristotle’s theories are based on old traditions; especially in view of the fact that racial ideas played such a role in Sparta.

The Tower of Babel and Nationalism

- And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech.

- And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there.

- And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them throughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for morter.

- And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

- And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded.

- And the LORD said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

- Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.

- So the LORD scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city.

- Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the LORD did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the LORD scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

My view of the necessary condition for nationalism:

Political Realism of John Mearsheimer

He is the author of the following six books:

Because I am interested in escaping from bullshit, I found his discussion with Vishnu Som on why leaders lie enlightening:

Also, the following discussion of his book, The Great Delusion, pretty much summarizes Mearsheimer’s views on international affairs:

The Odd Conservativism of Karl Popper

Although Popper is in agreement with Marx over the 19th century conditions suffered by workers under capitalism. But he is totally silent on the conditions suffered by people by the European colonization of the world. And he expressed the belief that it was British humanitarian attitudes that led to Britain granting independence to India. To show that I am not exaggerating, here is a quote from his article “The History of Our Time: An Optimist’s View” (1956) [reprinted in his Conjectures and Refutations (1963)]:

“When Mr Krushchev on his Indian tour indicated British colonialism, he was no doubt convinced of the truth of all he said. I do not know whether he was aware that his accusation were derived, via Lenin, largely from British sources. Had he known it, he would probably have taken it as an additional reason for believing in what he was saying . But he would have been mistaken; for this kind of self-accusation is a peculiarly British virtue as well as a peculiarly British vice. The truth is that the idea of India’s freedom was born in great Britain; as was the general idea of political freedom in modern times. And those Britishers who provided Lenin and Mr Krushchev with their moral ammunition were closely connected, or even identical, with those Britishers who gave India the idea of freedom.”

Since Popper wrote this in 1956, surely he must have known of the Jallianwals Bagh massacre in Amritsar, India in 1919. It was this and not abstract defense of freedom which caused Indians to rebel and Britain to concede.

Popper was against nationalism and the Wilsonian declaration for the right of self-determination.

“But the nationalist faith is equally absurd. I am not alluding here to Hitler’s racial myth. What I have in mind is, rather, an alleged natural right of man — the alleged right of a nation to self-determination. That even a great humanitarian and liberal like Masaryk could uphold this absurdity as one of the natural rights is a sobering thought. It suffices to shake one’s faith in the wisdom of philosopher kings, and it should be contemplated by all who think that we are clever but wicked rather than good but stupid. For the utter absurdity of the principle of national self-determination must be plain to anybody who devotes a moment’s effort to criticizing it. The principle amount to the demand that each state should be a nation-state: that it should be confined within a natural border, and that this border should coincide with the location of an ethnic group; so that it should be the ethnic group, the ‘nations’, which should determine and protect the natural limits of the state.” [same source]

When someone resorts to calling something “absurd” without an argument, critical rationalism has gone by the wayside.

See also: Centralization of power is not beneficial to ordinary people; it is bullshit.

Recently I came across a Ph.D. dissertation which squarely faces this issue: Craig Willkie, Open Nationalism: Reconciling Popper’s Open Society and the Nation State, University of Edinburgh, 2009.

See also: Andrew Vincent, “Popper and Nationalism,” in Karl Popper —A Centenary Assessment, Jarvie, Milford & Miller (eds), Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006.