Idealistic Theory of History = I think therefore I exist

Category: Historical Bullshit

Karl Popper on the Origin of the State

I have also greatly admired his scholarship. As an example, I reproduce his findings on the origin of the State through conquest — a position with which I agree. However, a fundamental disagreement that I have with Popper is whether the State can be dispensed with. He thinks the State is indispensable and can be justified. I disagree on both counts. But I leave this issue for another occasion.

Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, Chapter 4: footnote 43:

Plato’s remarkable theory that the state, i.e. centralized and organized political power, originates through a conquest (the subjugation of a sedentary agricultural population by nomads or hunters) was, as far as I know, first re-discovered (if we discount some remarks by Machiavelli) by Hume in his criticism of the historical version of the contract theory (cp. his Political Discourses, 1752, the chapter Of the Original Contract): — ‘Almost all the governments’, Hume writes, ‘which exist at present, or of which there remains any record in history, have been founded originally on usurpation or conquest, or both . . .’ The theory was next revived by Renan, in What is a Nation? (1882), and by Nietzsche in his Genealogy of Morals (1887); see the third German edition of 1894, p. 98. The latter writes of the origin of the ‘state’: ‘Some horde of blonde beasts, a conquering master race with a war-like organization . . lay their terrifying paws heavily upon a population which is perhaps immensely superior in — numbers. . . This is the way in which the “state” originates upon earth; I think that the sentimentality which lets it originate with a “contract”, is dead.’ This theory appeals to Nietzsche because he likes these blonde beasts. But it has been also more recently proffered by F. Oppenheimer (The State, transl. Gitterman, 1914, p. 68); by a Marxist, K. Kautsky (in his book on The Materialist Interpretation of History); and by W. G. Macleod (The Origin and History of Politics, 1931). I think it very likely that something of the kind described by Plato, Hume, and Nietzsche has happened in many, if not in all, cases. I am speaking only about ‘states’ in the sense of organized and even centralized political power.

I may mention that Toynbee has a very different theory. But before discussing it, I wish first to make it clear that from the anti-historicist point of view, the question is of no great importance. It is perhaps interesting in itself to consider how ‘states’ originated, but it has no bearing whatever upon the sociology of states, as I understand it, i.e. upon political technology (see chapters 3, 9, and 25).

Toynbee’s theory does not confine itself to ‘states’ in the sense of organized and centralized political power. He discusses, rather, the ‘origin of civilizations’. But here begins the difficulty ; for what he calls ‘civilizations’ are, in part, ‘states’ (as here described), in part societies like that of the Eskimos, which are not states; and if it is questionable whether ‘states’ originate according to one single scheme, then it must be even more doubtful when we consider a class of such diverse social phenomena as the early Egyptian and Mesopotamian states and their institutions and technique on the one side, and the Eskimo way of living on the other.

But we may concentrate on Toynbee’s description (A Study of History, vol. I, 305 ff.) of the origin of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian ‘civilizations’. His theory is that the challenge of a difficult jungle environment rouses a response from ingenious and enterprising leaders; they lead their followers into the valleys which they begin to cultivate, and found states. This (Hegelian and Bergsonian) theory of the creative genius as a cultural and political leader appears to me most romantic. If we take Egypt, then we must look, first of all, for the origin of the caste system. This, I believe, is most likely the result of conquests, just as in India where every new wave of conquerors imposed a new caste upon the old ones. But there are other arguments. Toynbee himself favours a theory which is probably correct, namely, that animal breeding and especially animal training is a later, a more advanced and a more difficult stage of development than mere agriculture, and that this advanced step is taken by the nomads of the steppe. But in Egypt we find both agriculture and animal breeding, and the same holds for most of the early ‘states’ (though not for all the American ones, I gather). This seems to be a sign that these states contain a nomadic element; and it seems only natural to venture the hypothesis that this element is due to nomad invaders imposing their rule, a caste rule, upon the original agricultural population. This theory disagrees with Toynbee’s contention (op. cit. III, 23 f.) that nomad-built states usually wither away very quickly. But the fact that many of the early caste states go in for the breeding of animals has to be explained somehow.

The idea that nomads or even hunters constituted the original upper class is corroborated by the age-old and still surviving upper-class traditions according to which war, hunting, and horses, are the symbols of the leisured classes; a tradition which formed the basis of Aristotle’s ethics and politics, and is still alive, as Veblen (The Theory of the Leisure Class) and Toynbee himself have shown; and to these traditions we can perhaps add the animal breeder’s belief in racialism, and especially in the racial superiority of the upper class. The latter belief which is so pronounced in caste states and in Plato and in Aristotle is held by Toynbee to be ‘one of the . . sins of our . . modern age’ and ‘something alien from the Hellenic genius’ (op. cit., III, 93). But although many Greeks may have developed beyond racialism, it seems likely that Plato’s and Aristotle’s theories are based on old traditions; especially in view of the fact that racial ideas played such a role in Sparta.

A Commentary on Howard Zinn’s “A People’s History of the United States”

At this point in time, my only criticism of Zinn’s book is that it did not focus sufficiently on land rights in the United States, as presented in such a book as: Charles Beard and Mary Beard, History of the United States, 1921; or such a book as: Roy M. Robbins, Our Landed Heritage: The Public Domain, 1776-1936, 1942. [A full copy is available for borrowing at Internet Archive.]

My point is that access to subsistence land is necessary for sheer animal existence, and such access in the British colonies was never free. Land was granted to individuals and corporations by the Kings of England, and these individuals and corporations had to create a profit for themselves and the King.

Below is an illustration of this from the Beards’ History:

Feudal Elements in the Colonies – Quit Rents, Manors, and Plantations. – At the other end of the scale were the feudal elements of land tenure found in the proprietary colonies, in the seaboard regions of the South, and to some extent in New York. The proprietor was in fact a powerful feudal lord, owning land granted to him by royal charter. He could retain any part of it for his personal use or dispose of it all in large or small lots. While he generally kept for himself an estate of baronial proportions, it was impossible for him to manage directly any considerable part of the land in his dominion. Consequently he either sold it in parcels for lump sums or granted it to individuals on condition that they make to him an annual payment in money, known as “quit rent.” In Maryland, the proprietor sometimes collected as high as £9000 (equal to about $500,000 to-day) in a single year from this source. In Pennsylvania, the quit rents brought a handsome annual tribute into the exchequer of the Penn family. In the royal provinces, the king of England claimed all revenues collected in this form from the land, a sum amounting to £19,000 at the time of the Revolution. The quit rent, – “really a feudal payment from freeholders,” – was thus a material source of income for the crown as well as for the proprietors. Wherever it was laid, however, it proved to be a burden, a source of constant irritation; and it became a formidable item in the long list of grievances which led to the American Revolution.Something still more like the feudal system of the Old World appeared in the numerous manors or the huge landed estates granted by the crown, the companies, or the proprietors. In the colony of Maryland alone there were sixty manors of three thousand acres each, owned by wealthy men and tilled by tenants holding small plots under certain restrictions of tenure. In New York also there were many manors of wide extent, most of which originated in the days of the Dutch West India Company, when extensive concessions were made to patroons to induce them to bring over settlers. The Van Rensselaer, the Van Cortlandt, and the Livingston manors were so large and populous that each was entitled to send a representative to the provincial legislature. The tenants on the New York manors were in somewhat the same position as serfs on old European estates. They were bound to pay the owner a rent in money and kind; they ground their grain at his mill; and they were subject to his judicial power because he held court and meted out justice, in some instances extending to capital punishment.

The manors of New York or Maryland were, however, of slight consequence as compared with the vast plantations of the Southern seaboard – huge estates, far wider in expanse than many a European barony and tilled by slaves more servile than any feudal tenants. It must not be forgotten that this system of land tenure became the dominant feature of a large section and gave a decided bent to the economic and political life of America. (Chapter 2)

After the American Declaration of Independence in 1776, a question arose as to the status of lands westward of the colonies. These eventually became known as the public domain, and by the Ordinance of May 20, 1785, the following measures went into effect:

In line with the earlier abolition of feudal incidents, the ordinance adopted allodial tenure, that is, land was to pass in fee simple from the government to the first purchaser. After clearing the Indian title and surveying the land the government was to sell it at auction to the highest bidder. Townships were to be surveyed six miles square and alternate ones subdivided into lots one mile square, each lot consisting of 640 acres to be known as a section. No land was to be sold until the first seven ranges of townships were marked off. A minimum price was fixed at $1 per acre to be paid in specie, loan-office certificates, or certificates of the liquidated debt, including interest. The purchaser was to pay surveying expenses of $36 per township. Congress reserved sections 8, 11, 26, and 29 in each township, and one-third of all precious metals later discovered therein. In addition the sixteenth section of each township was set aside for the purpose of providing common schools.[I add the following table:

[Robbins, Chapter I]

Township = 36 sections 6 5 4 3 2 1 7 8 9 10 11 12 18 17 16 15 14 13 19 20 21 22 23 24 30 29 28 27 26 25 31 32 33 34 35 36

Land was, thus, not available for free, and those who illegally settled on any land were squatters, who, when the surveys reached their land holdings had to pay or be booted out. The other major problem was that land was sold only in huge chunks; so that only wealthy speculators could afford to buy it, which they then resold to settlers for a profit.

As to the Homestead Act of 1862 which granted 160 acres for free; although Zinn points out that only inferior land was made available, he does not mention the exorbitant cost to the pioneer to undertake such a possession. See: Clarence H. Danhof, “FARM-MAKING COSTS AND THE “SAFETY VALVE”: 1850-60,” The Journal of Political Economy, Volume XLIX, Number 3, June 1941: 317-359.

In conclusion, I think that Zinn was right on target in the following excerpt in realizing that freedom from slavery without a free access to subsistence land is just another form of slavery — wage slavery.

Many Negroes understood that their status after the war, whatever their situation legally, would depend on whether they owned the land they worked on or would be forced to be semi-slaves for others. In 1863, a North Carolina Negro wrote that “if the strict law of right and justice is to be observed, the country around me is the entailed inheritance of the Americans of African descent, purchased by the invaluable labor of our ancestors, through a life of tears and groans, under the lash and yoke of tyranny.”Abandoned plantations, however, were leased to former planters, and to white men of the North. As one colored newspaper said: “The slaves were made serfs and chained to the soil. . . . Such was the boasted freedom acquired by the colored man at the hands of the Yankee.”

Under congressional policy approved by Lincoln, the property confiscated during the war under the Confiscation Act of July 1862 would revert to the heirs of the Confederate owners. Dr. John Rock, a black physician in Boston, spoke at a meeting: “Why talk about compensating masters? Compensate them for what? What do you owe them? What does the slave owe them? What does society owe them? Compensate the master? . . . It is the slave who ought to be compensated. The property of the South is by right the property of the slave. . . .”

Some land was expropriated on grounds the taxes were delinquent, and sold at auction. But only a few blacks could afford to buy this. In the South Carolina Sea Islands, out of 16,000 acres up for sale in March of 1863, freedmen who pooled their money were able to buy 2,000 acres, the rest being bought by northern investors and speculators. A freedman on the Islands dictated a letter to a former teacher now in Philadelphia:

My Dear Young Missus: Do, my missus, tell Linkum dat we wants land – dis bery land dat is rich wid de sweat ob de face and de blood ob we back. . . . We could a bin buy all we want, but dey make de lots too big, and cut we out.De word cum from Mass Linkum’s self, dat we take out claims and hold on ter um, an’ plant um, and he will see dat we get um, every man ten or twenty acre. We too glad. We stake out an’ list, but fore de time for plant, dese commissionaries sells to white folks all de best land. Where Linkum?

In early 1865, General William T. Sherman held a conference in Savannah, Georgia, with twenty Negro ministers and church officials, mostly former slaves, at which one of them expressed their need: “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and till it by our labor. . . .” Four days later Sherman issued “Special Field Order No. 15,” designating the entire southern coastline 30 miles inland for exclusive Negro settlement. Freedmen could settle there, taking no more than 40 acres per family. By June 1865, forty thousand freedmen had moved onto new farms in this area. But President Andrew Johnson, in August of 1865, restored this land to the Confederate owners, and the freedmen were forced off, some at bayonet point.

Ex-slave Thomas Hall told the Federal Writers’ Project:

Lincoln got the praise for freeing us, but did he do it? He gave us freedom without giving us any chance to live to ourselves and we still had to depend on the southern white man for work, food, and clothing, and he held us out of necessity and want in a state of servitude but little better than slavery.

Countries go to war because some individual decides to go to war

As I read political history, I am distracted from understanding what happened by such typical formulations as “Country X went to war with Country Y.” On some level of understanding this is true, but unenlightening. This is just as unenlightening as the recent report that Cornel West was denied tenure by Harvard. The more enlightening description of what happened is that Cornell West was denied the right to apply for tenure by the President of Harvard, Lawrence S. Bacow. And a still more enlightening account would probe into Bacow’s reasons. [ For an analogous case, see my analysis: Andrew Chrucky, “Norman Finkelstein, DePaul, and U.S. Academia: Reductio Ad Absurdum of Centralized Universities,” July 23, 2007]

My point is that when dealing with governed institutions — whatever their nature — it is a prevalent norm to describe these institution as if they were agents. But institutions are like tools or machines which require a particular human agent to use them. And what I am calling as “enlightened” description requires identifying the human agent who makes the machine operate, and it requires a further probing into that agent’s reasons for acting as he did.

Suppose you read in a newspaper that Jones was struck and killed by a car. OK, on one level this is a correct description. But if you want to get into a more enlightened description, you would want to know where and when this happened, what were the circumstances, and who was the driver. Was this an accident? What was the condition of the driver? Was this an intentional act? Deliberate?

I am proposing a similar sort of description for the actions of governments and countries. There is always some “decider” in the government (as President W. George Bush, Jr. described himself — accurately).

Let’s consider the infamous case of the U.S. dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

Such an act requires the decision of the Commander and Chief of the Armed Forces: the President of the United States. The responsible agent in this case was Harry S. Truman. And to get some enlightenment, we would need to understand his reasons.

Let’s consider another example. The fall of Constantinople in 1453. On one level, we can describe this event as a successful siege of Constantinople by the Turks. But on a more enlightening level, the siege was the decision of Sultan Mohammed II for whatever reasons.

What am I driving at? It is clear to me that great battles and wars are the decisions of powerful individuals. By “powerful,” I simply mean that they can get others to do what they want. They can use others as chess pawns for their ambitions. Who are these “pawns”? Soldiers and civilians!

Take any battle or war. On both sides, after the battle or war there are countless dead, disabled, sick and suffering. Consider the so-called American Civil War (1861-65). Wikipedia lists 616,222-1,000,000+ dead. Who was the decider who wanted to “preserve the union”? Abraham Lincoln!

Political history with its battles and wars, including the maintenance of internal “order,” is the history of megalomaniacs and other ambitious individuals who sacrifice the lives of countless others for their own profits and glory.

The lesson I draw from this reflection is that the principle of the separation of powers in government should include the separation of powers in the executive branch, as is done, for example, in Switzerland. Switzerland has a seven-member Federal Council; whereas everywhere else there is either a sole President, a Prime-Minister, or sometimes both.

Some Topic which I may or may not get to

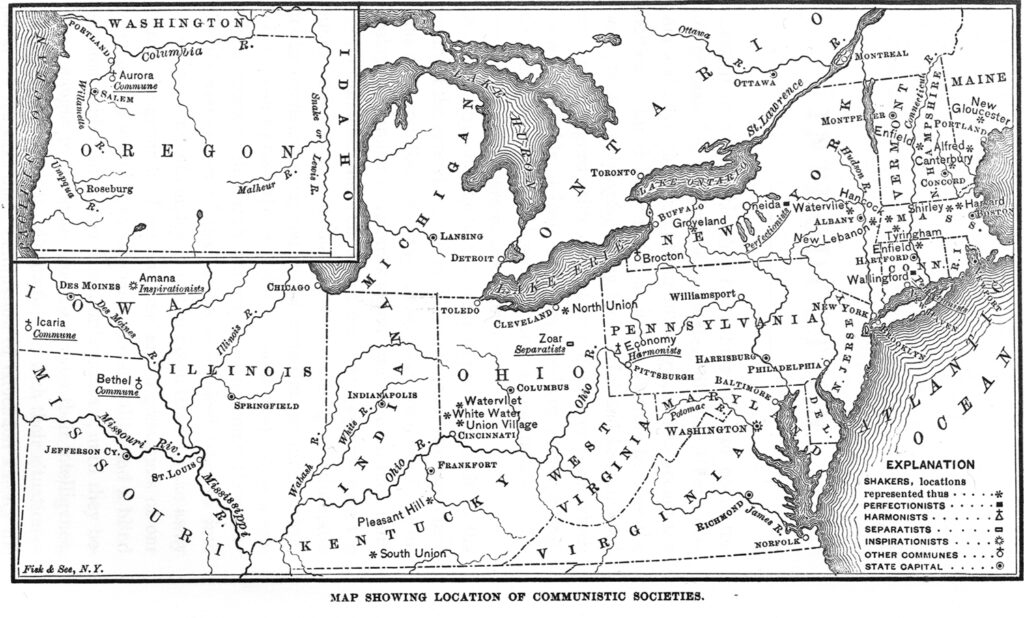

2. The experiment of Robert Owen in New Harmony, Indiana was a failed socialistic commune. And this example is often used to debunk the possibility of viable socialistic communes, calling them “utopias.” Such an example omits the very many successful socialistic — even communistic — communes and colonies. I have in mind as examples the various religious communes like the Rappists, who sold New Harmony to Owen, the Hutterites, the Shakers. the Amish, the Mennonites, the Dukhobors, and also such secular communes as the Kibbutzes in Israel. And let us not forget the many communities of Catholic monks and nuns.

Below is a map taken from Charles Nordhoff (1830-1901), The communistic societies of the United States, 1875.

3. Historians and others write as if countries were agents which go to war with each other. But the fact is that countries place war powers in single individuals (called monarchs, presidents, prime ministers). Take, for example, the United States which requires the formal approval of Congress to declare war. But wars can be engaged by Presidents by simply not calling the aggression a “war” — calling it “quelling a rebellion,” as did Abraham Lincoln.

An aggression can also be done in some other way by funding “freedom fighters,” or financing Contras in Nicaragua, or invading Panama to bring a culprit to justice, or invading Grenada to “protect U.S. citizens.” Or, by fabricating some reason for a preemptive attack on Iraq, and so on.

4. I am also bothered by the fact that World War I is not credited to Franz Joseph, the Emperor of Austria. Yes, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. But this could have been treated simply as a murder. How is it that a country was invaded for the act of a murderer? But it was not a simple murder. It was the murder of the son of the emperor’s brother! Whose will was this to seek this form of revenge? It was the will of Emperor, Franz Joseph!

Again, after the 9/11 attack, the highjackers all perished. Why was Afghanistan attacked? This was the decision of the “decider,” as George W. Bush, Jr. called himself.

However, with World War II, there is less hesitancy to blame a particular individual. Everyone blames Hitler. But there is always in wars and invasions some “decider” who has been given disastrous powers.

The difference between Yuval Harari and me

I, on the other hand, am more pessimistic. I see a world which is overpopulated and with fragile city structures, totally dependent on technologically operated capitalist governments and markets. And I anticipate that these systems will collapse. The education that is needed — when collapse occurs — is a sort of back to nature training — covered by such books as:

Further Commentary on Yuval Noah Harari’s book: Sapience: A Brief History of Mankind (2014)

Harari correctly recounts that humans underwent a Cognitive Revolution — his name for the evolutionary stage in which it became possible and actual for humans to acquire language, and this was followed by the subsequent stage of learning how to grow food and to herd animals — which can be called, as does Harari, the Agricultural Revolution.

Here Harari could have learned from Herman Nieboer’s Slavery: As an Industrial System (1900), that agricultural activity (and also “agricultural” fisheries) lend themselves to the rise of slavery through conquests. He could also have learned from Franz Oppenheimer’s The State, that these larger grouping of people, which we call States and Empires, are all the results of conquest. All subsequent history is, from this political perspective, a morphing of slavery, to serfdom, to wage-slavery. And, as Marx pointed out correctly, there is a correlation between these stages and the stages in the means of economic production.

So, my concern with history is the question: how did it transpire that I am a wage-slave? And how can I and others get out of this predicament?

This, however, is not Harari’s primary concern. His concern is a cognitive one: what made possible the Scientific Revolution and the prospects of Homo Deus?

Well, one ingredient is leisure. And this is achieved by others doing the work of supplying the necessities (and luxuries) of life. And leisure is achieved through conquest and slavery, serfdom, and capitalism. [Incidentally, I find his analysis of capitalism as requiring credit correct, but inadequate by omitting a discussion of the necessity of a proletarian class, and omitting a discussion of what makes such a class possible.]

Harari sees the movement of history as strivings for empire, and he recounts for us the various empires that have existed. And he notes which factors contribute to the unification of an empire: money, religion, and technology. [I would add a political order which maintains either slaves, serfs, or wage-slaves.] And he anticipates (and welcomes) the coming of a world empire. [Empires tend to assimilate various nationalities (languages) into one nationality (language). Harari welcomes this unification; I do not.]

We can appreciate and marvel at the achievements of great States and Empires: the architecture, the roads, the canals, the viaducts; and today, the various means of transportation, means of communication, means of harnessing energy, and the myriad uses and and fabrication of resources. This is all the result of the Scientific Revolution (preceded by a Renaissance and Protestant Reformation) which was aided by the existence of leisure — in other words, by the private and public support of scientists and creative people. But at what price? Slavery, serfdom, and wage-slavery.

I suppose the difference between me and Harari is over the ancient question of whether the end justifies the means. He seems to be end oriented. I am, on the other hand, means oriented. The means I seek are free agreements.

But as far as the trajectory of history is concerned he may be right that humankind will suffer either an ecological collapse or create a Homo Deus.

Comment from ethicalzac: May 27, 2020

I am so happy I discovered this site. I really cherish your insight but also enjoy Yuval Harari’s work. In my opinion I do not think Harari “welcomes the unification “(empire–consolidation of money and power, leaving people in its wake without agency).

What I think he’s saying is that if we (the rest of us) don’t come out with a new system or new stories that ultimately rehabilitate human agency then the stories (or narrative) of the status quo will win out. Consequently, the system will be churning out more and more useless people. That will live in a world handicapped by attachments, fiction and addiction. And that this world will be run by bullshit. Bullshit we witness everyday we turn the news on.

Harry Frankfurt made an awesome distinction between bullshitters and liars. The bullshitter has a selfish intention hidden at the core. While the liar does, in fact, know where the truth lies, the bullshitter doesn’t care,he has no conscious. Post Carter virtually all of the US Presidents were bullshit artists. Bush was woefully prepared to be one. But Clinton took the Gold. Obama the Silver and squirrel head the Bronze. (Trump was too old and showed cracks. Biden is coming across the same). All we have to do is stop this pathetic progression.

Reply by Chrucky: May 28, 2020

Thank you for the comment. In reply, I did not say that Harari welcomes any particular type of empire, but some kind of empire nonetheless. This is explicitly expressed under the heading “The New Global Empire.” (p. 207) His opening sentiments are the following: “Since around 200 BC, most humans have lived in empires. It seems likely that in the future, too, most humans will live in one. But this time the empire will be global. The imperial vision of dominion over the entire world could be imminent. . . .” From one perspective, this is just a prophecy, but it is a prophecy which he endorses. He could have said something to the effect that the United Nations — in some reformed way — should take charge. But this is not the route he recommends. And it is not clear what he does recommend.

(3) Further commentary on Ian Shapiro’s course: “Moral Foundations of Politics”

I agree with the idea of democracy as the claim that government, if moral, should be founded on the will of the people. However, Shapiro seems to use American Democracy, as if it were the paradigm of democratic government. My objection is that there are many different existing types of democratic governments, which Shapiro should have mentioned.

Shapiro mentioned Robert Dahl as being — according to him — the foremost current scholar of democracy. Because of this endorsement, I have read his book, On Democracy (1998). Dahl, in his turn, recommended looking at the freedom ranking of governments at the site: Freedom House. What is more interesting for me is the type of governments which exist in these “free” democracies. And for that answer — by Dahl’s recommendation — we should look at the studies of Arend Lijphart, whose most important book is Patterns of Democracy (1st ed. 1999; 2d ed. 2012). [available on the Internet]

Lijphart’s main classification of democracies is into two types: Majoritarian (also known as the Westminister model) and Consensus models. For example, the United Kingdom uses majoritarian democracy; whereas Switzerland uses consensus democracy.

I am not going to get into the details except to point out two features. In England the House of Commons is elected by a principle that whichever party gets the most votes wins, and then this party chooses the Prime Minister. Whereas in Switzerland, party members are elected by proportional representation, and the four parties with the largest number of representatives nominate the 7-member Federal Council.

Arend Lijphart believes that Consensus type of democracy is preferable to the Majoritarian type.

My criticism of Ian Shapiro’s course boils down to this. He failed to tell the audience that there are different types of democracies in the world, and failed to consider which is preferable.

But that is not his only failing: i.e., the failure to differentiate and to grade democracies. Beside actual different types of democracies, there are also ideal and utopian types of democracies which are never mentioned by Shapiro. For example, Part III “Utopia” of Robert Nozick’s Anarchism, State, and Utopia points in this direction. [Contrary to Nozick, I would call his framework for utopias as the framework for anarchism] And a general description of anarchist proposals could be summarized as bottom-up federated democracies.

And without considering these alternative ideal democracies, there is no prospect for finding “the moral foundations of politics.”

Professor Ian Shapiro’s course at Yale University: “Power and Politics in Today’s World”

Here is the syllabus for this course: Syllabus

Lecture 1: Introduction to Power and Politics in Today’s World

Lecture 2: From Soviet Communism to Russian Gangster Capitalism

Lecture 3: Advent of a Unipolar World: NATO and EU Expansion

Lecture 4: Fusing Capitalist Economics with Communist Politics: China and Vietnam

Lecture 5: The Resurgent Right in the West

Lecture 6: Reorienting the Left: New Democrats, New Labour, and Europe’s Social Democrats

Lecture 7: Shifting Goalposts: The Anti-Tax Movement

Lecture 8: Privatizing Government I: Utilities, Eminent Domain, and Local Government

Lecture 9: Privatizing Government II: Prisons and the Military

Lecture 10: Money in Politics

Lecture 11: Democracy’s Fourth Wave? South Africa, Northern Ireland, and the Middle East

Lecture 12: Business and Democratic Reform: A Case Study of South Africa

Lecture 13: The International Criminal Court and the Responsibility to Protect

Lecture 14: 9/11 and the Global War on Terror

Lecture 15: Demise of the Neoconservative Dream From Afghanistan to Iraq

Lecture 16: Denouement of Humanitarian Intervention

Lecture 17: Filling the Void – China in Africa

Lecture 18: Political Limits of Business: The Israel-Palestine Case

Lecture 19: Crisis, Crash, and Response

Lecture 20: Fallout: The Housing Crisis and its Aftermath

Lecture 21: Backlash – 2016 and Beyond

Lecture 22: Political Sources of Populism – Misdiagnosing Democracy’s Ills

Lecture 23: Building Blocks of Distributive Politics

ecture 24: Unemployment, Re-employment & Income Security

Lecture 25: Tough Nuts – Education and Health Insurance

Lecture 26: Agendas for Democratic Reform

Power and Politics in Today’s World – Office Hours 1: The Collapse of Communism and its Aftermath

Power and Politics in Today’s World – Office Hours 2: The Collapse of Communism and its Aftermath II

Power and Politics in Today’s World – Office Hours 3: A New Global World Order?

Power and Politics in Today’s World – Office Hours 4: The End of the End of History

Power and Politics in Today’s World – Office Hours 5: The Politics of Insecurity