Andrew Chrucky

Let me explain. He espouses critical thinking, but he seems to confine this criticism to exposing pseudo-science and superstitions, including a criticism of religion. But such criticism was already done during the Enlightenment, and those who have not absorbed these criticisms are The Unenlightened. As to the existence of God, there is no need to duplicate such articles as that of C.D. Broad’s Arguments for the Existence of God and The Validity of Belief in a Personal God. As to debunking pseudoscience, there is Martin Gardner’s Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science.

Debunking of this sort is fine, but a critical thinker must distinguish between important problems and puzzles. The important problems are “existential,” by which I mean those problems which hinder human animal existence: problems of food, water, shelter, and such. These are economic and political problems.

I wanted to find out Shermer’s stance on political and economic issues. What I found out so far is that he seems to be a moderate conservative. By this I mean that he accepts capitalism and the type of liberal (mass, macro) democracy as found in the United States. His concern is to improve the policies of the government of the United States — like abortion or immigration policies. He is not concerned with, for example, comparing the democratic government of the United States with that of Switzerland. And he seems to be oblivious to an anarchistic federalist alternative. And because he does not consider such varieties of democracy, he is — in my view — myopic.

As an example of what I am saying, let’s consider his latest interview with Brian Klaas, the author of Corruptible: Who Gets Power and How It Changes Us, 2021. Here is the interview:

Comment: Klaas is interested in the question whether corruptible people seek power or whether power corrupts? And Klaas said that his question is ultimately how to fix the system. Both were interested in how to better recruit leaders. But it never even came up to ask the question of whether instead of a single leader, such as a President or a Prime Minister, a Federal Council of seven individuals, as exists in Switzerland, was preferable.

Klaas made a distinction between a dysfunctional democracy and a functional democracy. But what alternative democracies are possible never even came up, except for a sortition (lottery) shadow parliament.

Shermer thinks that the United States is a functional democracy. His criterion of a functional democracy seems to be whether there is free and universal mass voting. That’s all. He also was non-critical about promoting liberal democracy around the world, including Iraq and Afghanistan. The fact that both countries were invaded by the United States was — as it were — justified if the US was successful in promoting liberal democracy. And Shermer seems to be ok with the hundreds of US military posts around the world, and proposed that some troops should have remained in Afghanistan.

My impression is that he is playing it politically safe with liberal democracy in having an ongoing popular talk show.

by Sheldon S. Wolin, Newsday, July 18, 2003

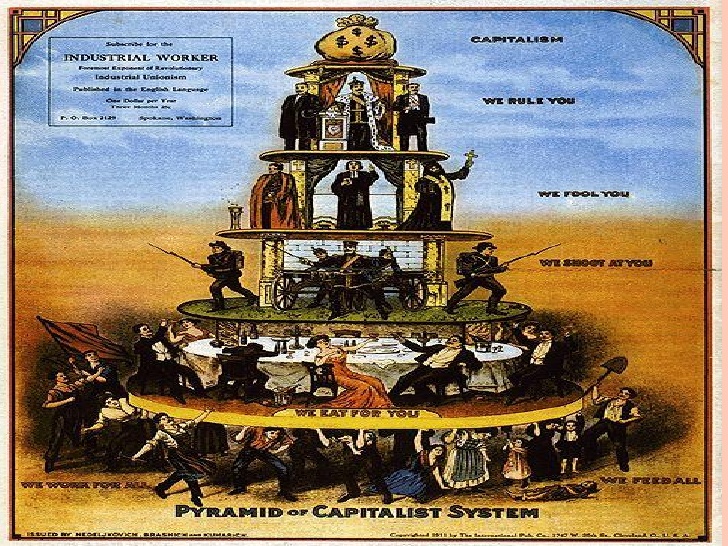

Instead of those formulations, try to conceive of ones like “superpower democracy” or “imperial democracy,” and they seem not only contradictory but opposed to basic assumptions that Americans hold about their political system and their place within it. Supposedly ours is a government of constitutionally limited powers in which equal citizens can take part in power. But one can no more assume that a superpower welcomes legal limits than believe that an empire finds democratic participation congenial.

No administration before George W. Bush’s ever claimed such sweeping powers for an enterprise as vaguely defined as the “war against terrorism” and the “axis of evil.” Nor has one begun to consume such an enormous amount of the nation’s resources for a mission whose end would be difficult to recognize even if achieved.

Like previous forms of totalitarianism, the Bush administration boasts a reckless unilateralism that believes the United States can demand unquestioning support, on terms it dictates; ignores treaties and violates international law at will; invades other countries without provocation; and incarcerates persons indefinitely without charging them with a crime or allowing access to counsel.

The drive toward total power can take different forms, as Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union suggest.

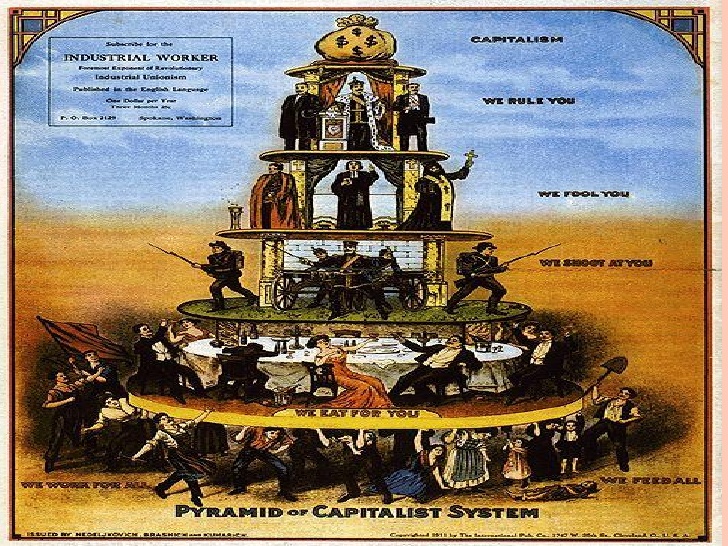

The American system is evolving its own form: “inverted totalitarianism.” This has no official doctrine of racism or extermination camps but, as described above, it displays similar contempt for restraints.

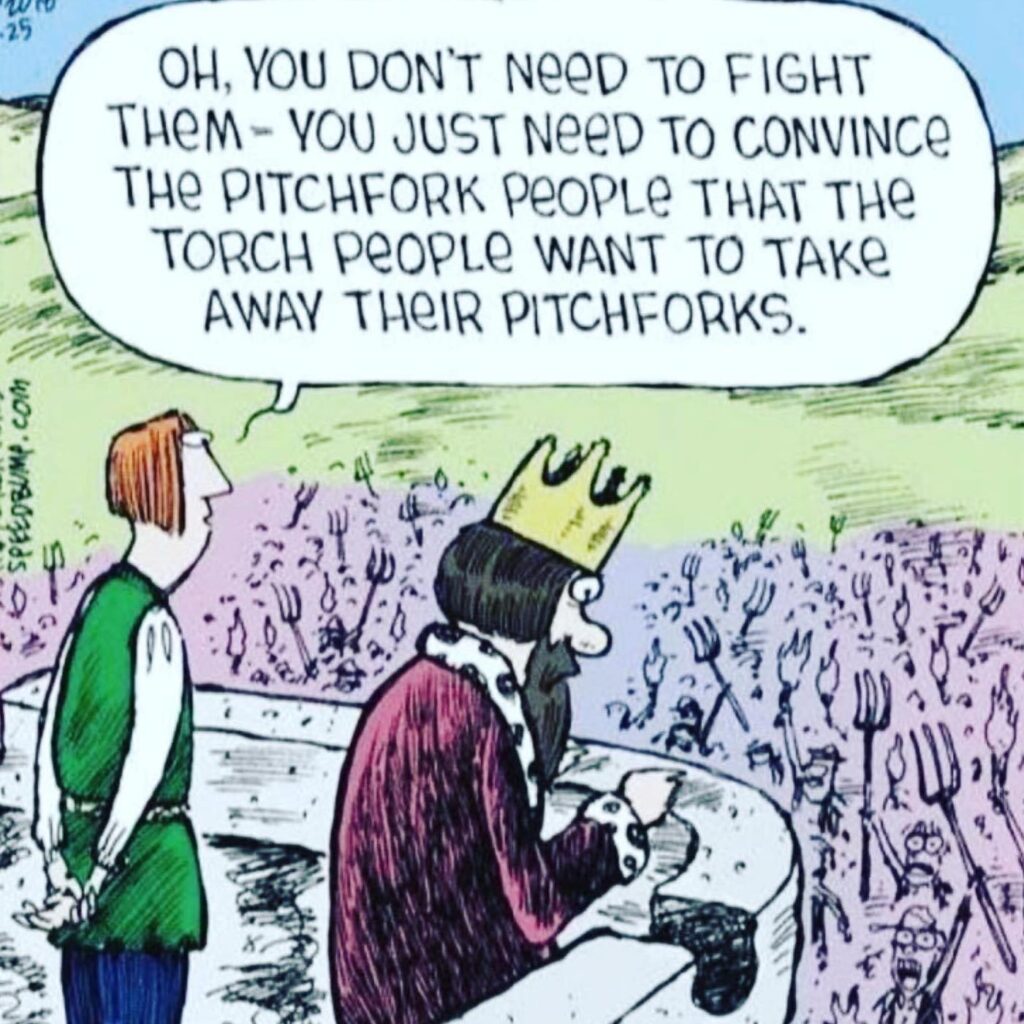

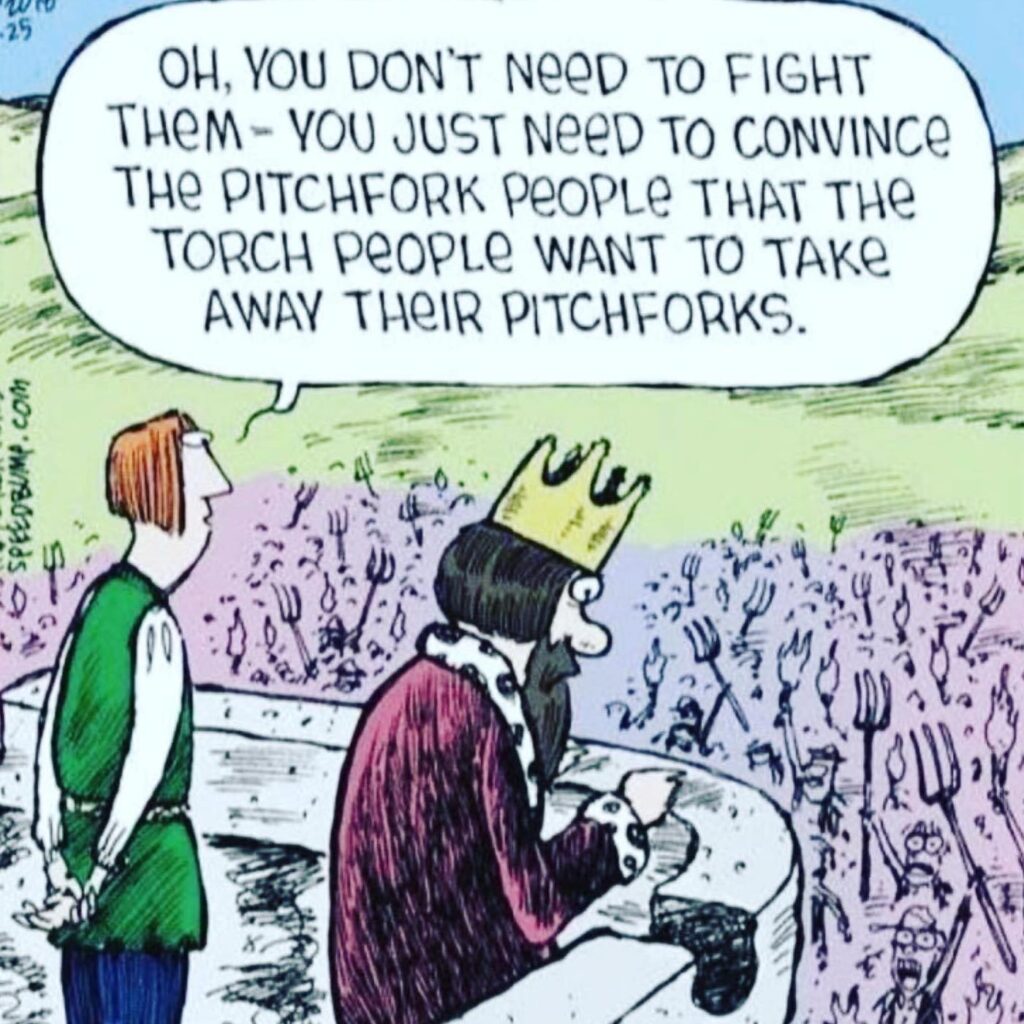

It also has an upside-down character. For instance, the Nazis focused upon mobilizing and unifying the society, maintaining a continuous state of war preparations and demanding enthusiastic participation from the populace. In contrast, inverted totalitarianism exploits political apathy and encourages divisiveness. The turnout for a Nazi plebiscite was typically 90 percent or higher; in a good election year in the United States, participation is about 50 percent.

Another example: The Nazis abolished the parliamentary system, instituted single-party rule and controlled all forms of public communication. It is possible, however, to reach a similar result without seeming to suppress. An elected legislature is retained but a system of corruption (lobbyists, campaign contributions, payoffs to powerful interests) short-circuits the connection between voters and their representatives. The system responds primarily to corporate interests; voters become cynical, resigned; and opposition seems futile.

While Nazi control of the media meant that only the “official story” was communicated, that result is approximated by encouraging concentrated ownership of the media and thereby narrowing the range of permissible opinions.

This can be augmented by having “homeland security” envelop the entire nation with a maze of restrictions and by instilling fear among the general population by periodic alerts raised against a background of economic uncertainty, unemployment, downsizing and cutbacks in basic services.

Further, instead of outlawing all but one party, transform the two-party system. Have one, the Republican, radically change its identity:

From a moderately conservative party to a radically conservative one.From a party of isolationism, skeptical of foreign adventures and viscerally opposed to deficit spending, to a party zealous for foreign wars.

From a party skeptical of ideologies and eggheads into an ideologically driven party nurturing its own intellectuals and supporting a network that transforms the national ideology from mildly liberal to predominantly conservative, while forcing the Democrats to the right and and enfeebling opposition.

From one that maintains space between business and government to one that merges governmental and corporate power and exploits the power-potential of scientific advances and technological innovation. (This would differ from the Nazi warfare organization, which subordinated “big business” to party leadership.)

The resulting dynamic unfolded spectacularly in the technology unleashed against Iraq and predictably in the corporate feeding frenzy over postwar contracts for Iraq’s reconstruction.

In institutionalizing the “war on terrorism” the Bush administration acquired a rationale for expanding its powers and furthering its domestic agenda. While the nation’s resources are directed toward endless war, the White House promoted tax cuts in the midst of recession, leaving scant resources available for domestic programs. The effect is to render the citizenry more dependent on government, and to empty the cash-box in case a reformist administration comes to power.

Americans are now facing a grim situation with no easy solution. Perhaps the just-passed anniversary of the Declaration of Independence might remind us that “whenever any form of Government becomes destructive …” it must be challenged.