G. A. Cohen: Criticism of Capitalism

Jerry Cohen is the Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory and Fellow of All Souls Oxford. In tonight’s opinions, he argues that capitalism deprives people of their rightful share in the world’s resources, and it frustrates the satisfaction of fundamental human needs.

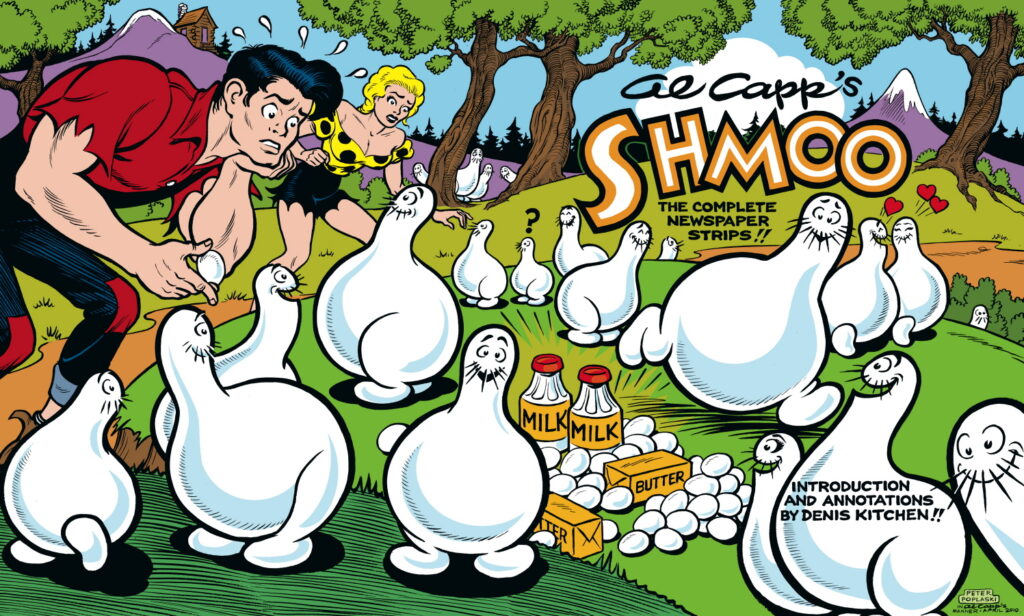

I’m going to start with a story which was told by the American cartoonist Al Capp. The story’s about a creature called the Shmoo. The Shmoo was 10 inches high, something like a pear in shape, and a beautiful creamy white in color. It had no arms, tiny feet, and big whiskers under its nose. The Shmoo had only one desire: to serve the needs of human beings. And it was well equipped to do so. It’s skin could be made into any kind of fabric. Its flesh was edible. Its dead body could go brick hard, and be used for building, and its whiskers — well its whiskers — had more uses than you can imagine. If you looked at a Shmoo with real hunger in your eye, it dropped dead in rapture because you wanted it, after first cooking itself into your favorite flavor. Well, since they multiplied rapidly, there were plenty of schmoos for everybody, and they even looked good in the environment. Almost everyone approved of the schmoos. But some people weren’t keen on them. The rich capitalists hated the Shmoos. Since Shmoos provided everything people needed, nobody had to work for capitalists anymore because nobody had to make the wages to buy the things capitalists sold. And so as the Shmoos spread across the face of America, the capitalists began to lose their position and their power. And this made them take drastic action. They got the government to tell the people that the Shmoo was un-American. The Shmoo was causing chaos, undermining the social order, people weren’t turning up for work, and they weren’t going to the department stores to buy anything. Well, the government propaganda, convinced the people, and the President ordered the FBI to gather the Shmoos and gunned them down. Then things went back to normal. But a country lad called Li’l Abner managed to save one female and one male Shmoo. He carried them off to a distant valley where he hoped they’d be safe. “Folks ain’t yet ready for the Shmoo,” Li’l Abner said. But Li’l Abner was wrong. Folks were ready for the Shmoo. It was only the capitalists that weren’t. The capitalists didn’t like the Shmoo because it gave people independence. And when people don’t depend on them for work and for goods, capitalists lose their privileged place.

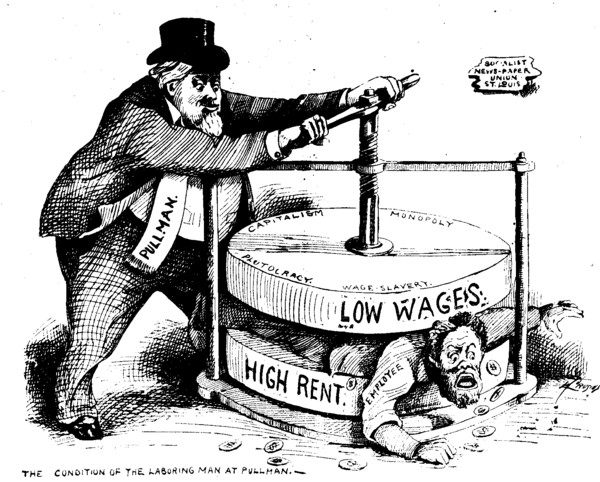

People haven’t always depended on capitalists. They never, of course, had Shmoos. But they did have land. And the things they get from Shmoos in Al Capp story, they got by working the land in pre-capitalist history. It’s true that they didn’t keep everything they produced on the land. Monarchs and their hangers-on, and various lords and ladies were usually able to take quite a bit of their product. But the people didn’t depend for their survival on any superiors until after a long history of forced expropriation, and plain and crooked dealing, they found themselves without any resources for producing things except their own labor. And in order to survive, they had to hire themselves out to capitalists who now had all the other resources. So they got a new set up. And in this new set up, workers sold their labor and capitalists bought it. And the buyers treated the sellers as nothing but sources of profit. So when the buyers didn’t need all the labor that was offered, some workers were denied employment. And since they had no land or Shmoos to live off, they became beggars, and vagabonds, and inmates of work houses. Or, they simply wasted away.

Well, of course things aren’t quite that bad now. Capitalism isn’t as pure and ruthless as it used to be. The dispossessed workers defended themselves by uniting and trade unions and the coming of the welfare state with its public provision of necessities means that workers don’t depend for everything they need on finding someone who wants to buy their labor. The trade unions and the welfare state were savagely resisted by the capitalists, but they’ve come to stay now.

Now, advocates of pure capitalism describe it as a system in which people freely exchange their own private property. Socialists denied the freedom and fairness of that exchange. They complain that some are able to bring vast assets to market, while most people have nothing to sell except their own capacity to work. That’s the socialist complaint.

But against that socialist complain, lots of capitalists will say, “Hang on a minute, wait a second. It’s true that I have vast assets now, but I started with practically nothing except my own talent and courage. And it was by using them that I made my pile. You can’t talk about lack of fairness. I had no unfair advantage in the race for wealth.”

Well, the socialists might reply that it’s pretty rare these days for a capitalist to begin with brains and grit alone. But I want to focus here on just such self-made capitalists, since their wealth does look pretty legitimate. Well, if you think about that. Wealth, what’s it made of, in its immediate form? It’s just bits of paper, records and Leisure’s share certificates, and so on. But the reason why those things are valuable is that they entitle their possessor to material resources — to raw and transformed parts of nature, to iron ore that’s been turned into steel, to factories, and energy, and power lines, and tracts of land, and minerals under the sea. The capitalist is happy to tell us how he got all that stuff. He says, “Look, I got it through my own hard work and enterprise. I didn’t get it from my parents. I didn’t get it by stealing or cheating.”

But we can ask a deeper question — a question which is much more difficult for him to answer, a question which is prompted by the realization that everything he owns — everything either is or was made of something which once was nobody’s private property. The deep question is: how did it come to be anybody’s private property in the first place? You see, the capitalist says that he got his wealth through free market exchange, and that means that he’s defending his title to it by invoking the title of those who transferred it to him. But I’m asking: what was the source of their right to it? The fact that they got it from still earlier owners. Well, that kind of justification can’t go on forever. Eventually we’re going to be pushed back to the very first private owners of land and the raw materials of nature. And they didn’t get them from earlier legitimate owners. They simply took nature’s resources. And I’m asking: what gave them the right not merely to use the world, because that’s okay, but to establish permanent bequeathable private property in it so that others could no longer use it freely. What gave that right?

The self-made capitalist explains how: through honest industry and straight dealing, he accumulated an enormous amount of private property. But why was there that private property to accumulate in the first place? No story about the exchange and accumulation of private property can justify the transformation of things into private property in the first place. The fact that the world’s resources were once privately owned by nobody, and then grabbed, supports the socialist idea that they should be restored to the people as a whole.

But now, I want to look at a different line of defense of capitalism which says: “Come on, forget about past history. Let bygones be bygones. Don’t be obsessed with the misty origins of capitalism. It doesn’t matter how capitalist property came into being. Whatever the origin of capitalism was, it’s an excellent system since even the poorest people do better under capitalism than they would in any other form of economy.”

Well, the argument for the idea that capitalism promotes human benefit is pretty familiar. It goes something like this. Capitalist firms survive only if they make money. And they make money only if they prevail in competition against other capitalist firms. Since that competition is severe, the firm to survive has to be efficient. If firms producing incompetently, they go under. so they have to seize every opportunity to improve their productive facilities and techniques so that they can produce cheaply enough to make enough money to go on. Its admitted in this justification of capitalism that the capitalist firm doesn’t aim to satisfy people, but the firms can’t get what they are aiming at — which is money — unless they do satisfy people, and satisfy them better than rival firms do.

Well, I agree with part of this argument. Capitalist competition that has to be acknowledged has induced a remarkable growth in our power to produce things. But the argument also says that capitalism satisfies people. And I’m going to claim that the way the system uses technical progress generates widespread frustration; not satisfaction.

My anti-capitalist argument starts with the very same proposition with which the argument praising capitalism begins, namely this proposition: the aim of the capitalist firm is to make as much money as it can. It isn’t basically interested in serving anybody’s needs. It measures its a performance by how much profit it makes. Now, that doesn’t prove straight off that it isn’t good at serving need. In fact, the case for capitalism that I expressed a moment ago, might be put as follows: Competing firms trying not to satisfy needs but to make money, will in fact serve our needs extremely well since they can’t make money unless they do so. Okay, that’s the argument.

But I’m now going to show that the fact that capitalist firms aren’t interested in serving human needs, does have harmful consequences. Recall that improvement in productivity is required if the firm is going to survive in competition. Now, what does improve productivity mean? It means more output for every unit of labor. And that means that you can do two different things when productivity goes up. One way of using enhanced productivity is to reduce work and extend leisure, while producing the same output as before. Alternatively, output may be increased while labor stays the same. Now, let’s grant that more output is a good thing. But it’s also true that for most people, what they have to do to earn a living, isn’t a source of joy. Most people’s jobs, after all, are such that they benefit not only from more goods and services, but also from a shorter working day and longer holidays. Just consider, if God gave all of us the pay we now get, and granted us freedom to choose whether or not to work at our present jobs for as long as we pleased, but for no extra pay, then there’d be a big increase in leisure time pursuits. So, improved productivity makes two things possible. It makes possible either more output or less toil. Or, of course, some mixture of both.

But capitalism is biased in favor of the first option only: increased output, since the other reduction of toil threatens a sacrifice of the profit associated with greater output and sales. What does the firm do when the efficiency of its production improves? Well, it doesn’t just reduce the working day of its employees and produce the same amount as before, instead it makes more stuff. It makes more of the goods it was already making. Or, if that isn’t possible, because the demand for what it’s selling won’t expand, then it lays off part of its workforce and seeks a new line of production in which to invest the money it thereby saves. Eventually new jobs are created, and output continues to expand although there’s a lot of unemployment and suffering along the way.

Now the consequence of the increasing output which capitalism favors is increasing consumption. And so, we get an endless chase after consumer goods just because capitalist firms are geared to making money, and not to serving the interests of consumers. Alfred P. Sloan, who once ran General Motors in the United States, said that it was the business of the automobile industry to make money; not cars. I agree. And that I’m saying is why it makes so many cars. It would make far fewer if its goal weren’t money but, say, providing people with an efficient and an inoffensive form of transport. If the aim of production were the satisfaction of need, then rather less would be produced and consumed than is in fact produced and consumed. And most of us would lead less anxious lives and have more time and energy for the cultivation and enjoyment of our own powers.

Now, I am not some kind of fanatical Puritan who’s against consumer goods. I’m not knocking consumer goods. Consumer goods are fine. But the trouble with the chase after goods in a capitalist society is that we’ll always — most of us — want more goods than we can get, since the capitalist system operates to ensure that people’s desire for goods is never satisfied. Business, of course, wants contented customers but they mustn’t become too contented, since when customers are satisfied with what they’ve got, they buy less and work less. And business dwindles. That’s why in a capitalist society, an enormous amount of effort and talent goes into trying to get people to want what they don’t have. That’s why there’s feverish product innovation, huge investments in sales and advertising, and planned obsolescence. In order to keep going as a system, capitalism has to keep people on the go, and it creates a great deal of strain and nervous tension. The Rockefellers make sure that the Smiths need to keep up with the Joneses. And in a forlorn attempt to keep up because not everybody can manage to keep up. People work their lives away, and sometimes take extra jobs in order to buy things they don’t have the time to enjoy because of the time they spend working to buy them. Well, in earlier periods of capitalist history, its preference for output conferred on the system a progressive historical role. Capitalism raised us above the scarcity imposed by nature under which pre-capitalist peasants labored. But as that natural scarcity recedes, the output preference renders capitalism reactionary. It can’t realize the possibilities of liberation it creates. Having lifted the burden of natural scarcity, it contrives an artificial scarcity which means that people never feel they have enough. Capitalism brings humanity to the very threshold of liberation and then locks the door. We get near it, but we remain on a treadmill just outside it. Sometimes people fall off that treadmill. And recently in this country, that’s happened on a large scale. I’m referring again to the problem of unemployment which is now enormous in Britain. The same system that overworks people in the interest of profit also deprives them entirely of when it’s not profitable to employ them. And what we get as a result is not something that we could imagine: a reasonable amount of work, and a balanced existence for everyone, but grotesque over employment for some, together with rending unemployment for others. How can they say that this system satisfies human need when homeless people in Britain need housing and unemployed bricklayers need work? How can anybody think that it’s a system that promotes human benefit when it projects the message that the only way to self esteem is to be the owner of a BMW, or at least a Ford Sierra? And then it throws millions of families into a destitution where they can barely afford sausages to feed their children. So, I’m very skeptical about the claim that capitalism is so good at satisfying our needs as consumers. And anyway, people have needs which go beyond the need to consume.

One of those needs will — because it’s so important — occupy most of the rest of this talk: it’s a person’s need to develop and exercise his or her talents. When people’s capacities lie unused they don’t enjoy the zest for life which comes when their faculties flourish. Now, people are able to develop themselves only when they get good education. But in a capitalist society, the education of children is threatened by those who seek to fit education to the narrow demands of the labour market. And some of them think that what’s now needed to restore profitability to an ailing British capitalism is a lot of cheap unskilled labour. And they conclude that education should be restricted to ensure that it’ll supply that labour.

The present Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Lawson, said in a speech a couple of years ago that we should now think about training people for jobs which are — as he put it — not so much low-tech as no tech. Now, what sort of education is contemplated in that snappy statement, “Not so much low-tech as no tech”? Not an education that nourishes the creative powers of young people, and brings forth their full capacity. Nigel Lawson is saying that it’s dangerous to educate the young too much because then we produce cultivated people who aren’t suited to the low-grade jobs the market will offer them. An official at the Department of Education and Science recently said something similar. He said — and I’m here quoting his words — “that we are beginning to create aspirations which society cannot match. When young people can’t find work which meets their abilities and expectations, then we’re only creating frustration with disturbing social consequences. We have to ration educational opportunities so that society can cope with the output of education. People must be educated once more to know their place.” That’s the end of the quote.

But what if we got here? Something very frightened. We’ve got a policy of deliberately restricting educational provision so that state schools can produce willing sellers of low-grade labor power. It’s hard to imagine a more undemocratic approach to education. And notice that to prefer a democratic distribution of educational opportunity, you don’t have to believe that everyone is just as clever as everyone else. Nigel Lawson isn’t saying that most people are too dimmed to benefit from a high level of education. It’s precisely because people respond well to education that the problem which worries him arises. You see, there’s a lot of talent in almost every human being. You can see it in kids. But in most people that talent remains undeveloped since they haven’t had the time and the freedom and the facilities to develop it. Throughout history, only a leisured minority have enjoyed such freedom on the backs of the toiling majority. And that’s been unavoidable up to now. But now it’s no longer unavoidable. We have a superb technology which could be used to restrict unwanted labour to a modest place in life. But capitalism doesn’t use that technology in a liberating way. It continues to imprison people in largely unfulfilling work. And it shrinks from providing the enriching education which the technology it has created makes possible.

Some supporters of British capitalism disagree with Lawson’s idea that there’s a danger that people will get too much education. They say that what the market now needs is a better trained labor force. Well, whoever’s right about that, I’m confident that we shouldn’t stake our children’s future on the hope that the capitalist market will need what’s good for them. The educational system shouldn’t be subject to the capricious demands of capitalism. And it shouldn’t cater to the tendency of capitalism to treat enormous numbers of people as nothing but sources of profit. And when they can’t be profitably exploited, as redundant and expendable, because that’s what the capitalist firm does.

Is it possible to create a society which goes beyond the unequal treatment that capitalism imposes? Many would say that the idea of such a society is an idle dream. Many would agree with the negative things I’ve said about capitalism. But they’d say, “Look, there’s no point getting upset about it. There’s always been inequality of one kind or another, and there always will be.”

But I think that reading of history is too pessimistic. There’s actually much less inequality now than there was, for instance, a hundred years ago. A hundred years ago, only a few radicals proposed that everybody should have the vote. Others thought that was a dangerous idea. And most would have considered it to be an unrealistic one. But today we have the vote. We are a political democracy. But we’re not an economic democracy. We don’t share our material resources. And most people in this country would regard that as an unrealistic idea. Yet, I’m sure it’s an idea whose time will come. Society won’t always be divided into those who control its resources and those who have only their own labour to sell. But it’ll take a lot of thought to work out the design of a democratic economic order. And it’ll take a lot of struggle against privilege and power to bring it about. We can’t go back to being independent peasant communities, and even if we could, we’d be sacrificing the tremendous gains we owe to capitalism if we did so nor is anybody going to provide us with Shmoos. The obstacles to economic democracy are considerable. But just as no one now would defend slavery or serfdom, I believe that a day will come when no one will be able to defend a form of society in which a minority profit from the dispossession of the majority