Author: chrucky

The “Permanent War State” Aims to Plunder Venezuela

How not to argue

Carlson’s retort is typical of people who are put in a corner with no reasonable response.

Where on Paul Graham’s hierarchy of disagreement pyramid does Carlson’s reply belong?

Taxes, Taxes, Taxes, . . . the rest is bullshit

In the first video below is the discussion at Davos in which Bregman made his points.

In the second video, The Young Turks (TYT) comment on the exchange between Tucker Carlson and Rutger Bregman. Carlson invited Bregman to talk about the phenomenon of tax avoidance . . . but it never got there. Instead, Bregman focused on the problem of why such an issue as tax avoidance is not discussed by the major media, and his own answer was it is because billionaires pay millionaires — like Tucker Carlson — not to discuss it. At that point Carlson lost his composure with an emotive reaction of “go fuck yourself!”

The third video is the full exchange between Carlson and Bregman.

Video 1:

Video 2:

Video 3:

In the following clip, Noam Chomsky made the same charge against an interviewer as did Bregman against Carlson.

The Tyranny of Words

Take, for example, the label “fascism.” Stuart Chase, in his book, appropriately titled The Tyranny of Words, 1938, asked many people to tell him what “fascism” meant for them. Below is his take on “fascism,” and the result of his survey.

Pursuit of “fascism.” As a specific illustration, let us inquire into the term “fascism” from the semantic point of view. Ever since Mussolini popularized it soon after the World War, the word has been finding its way into conversations and printed matter, until now one can hardly go out to dinner, open a newspaper, turn on the radio, without encountering it. It is constantly employed as a weighty test for affairs in Spain, for affairs in Europe, for affairs all over the world. Sinclair Lewis tells us that it can happen here. His wife, Dorothy Thompson, never tires of drawing deadly parallels between European fascism and incipient fascism in America. If you call a professional communist a fascist, he turns pale with anger. If you call yourself a fascist, as does Lawrence Dennis, friends begin to avoid you as though you had the plague.

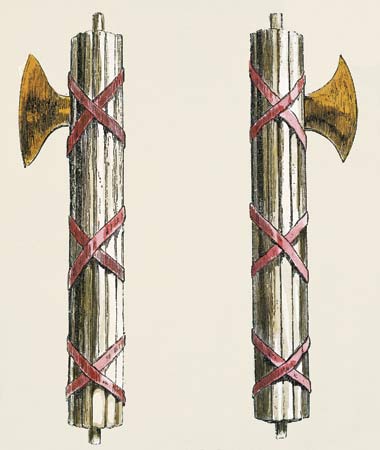

In ancient Rome, fasces were carried by lictors in imperial processions and ceremonies. They were bundles of birch rods, fastened together by a red strap, from which the head of an axe projected. The fasces were symbols of authority, first used by the Roman kings, then by the consuls, then by the emperors, A victorious general, saluted as “Imperator” by his soldiers, had his fasces crowned with laurel.

Mussolini picked up the word to symbolize the unity in a squad of his black-shirted followers. It was also helpful as propaganda to identify Italy in 1920 with the glories of imperial Rome. The programme of the early fascists was derived in part from the nationalist movement of 1910, and from syndicalism. The fascist squadrons fought the communist squadrons up and down Italy in a series of riots and disturbances, and vanquished them. Labour unions were broken up and crushed.

People outside of Italy who favoured labour unions, especially socialists, began to hate fascism. In due time Hitler appeared in Germany with his brand of National Socialism, but he too crushed labour unions, and so he was called a fascist. (Note the confusion caused by the appearance of Hitler’s “socialism” among the more orthodox brands.) By this time radicals had begun to label anyone they did not like as a fascist. I have been called a “social fascist” by the left press because I have ideas of my own. Meanwhile, if the test of fascism is breaking up labour unions, certain American communists should be presented with fasces crowned with laurel.

Well, what does “fascism” mean? Obviously the term by itself means nothing. In one context it has some meaning as a tag for Mussolini, his political party, and his activities in Italy. In another context it might be used as a tag for Hitler, his party, and his political activities in Germany. The two contexts are clearly not identical, and if they are to be used one ought to speak of the Italian and German varieties as facism1 and fascism2.

More important than trying to find meaning in a vague abstraction is an analysis of what people believe it means. Do they agree? Are they thinking about the same referent when they hear the term or use it? I collected nearly a hundred reactions from friends and chance acquaintances during the early summer cf 1937. I did not ask for a definition, but asked them to tell me what “fascism” meant to them, what kind of a picture came into their minds when they heard the term. Here are sample reactions:

Schoolteacher: A dictator suppressing all opposition.

Author: One-party government. “Outs” unrepresented.

Governess: Obtaining one’s desires by sacrifice of human lives.

Lawyer: A state where the individual has no rights, hope, or future.

College Student: Hitler and Mussolini.

United Stales senator: Deception, duplicity, and professing to do what one is not doing.

Schoolboy: War. Concentration camps. Bad treatment of workers. Something that’s got to be licked.

Lawyer: A coercive capitalistic state.

Teacher: A government where you can live comfortably if you never disagree with it.

Lawyer; I don’t know.

Musician: Empiricism, forced control, quackery.

Editor: Domination of big business hiding behind Hitler and Mussolini.

Short story writer: A form of government where socialism is used to perpetuate capitalism.

Housewife: Dictatorship by a man not always intelligent.

Taxi-driver: What Hitler’s trying to put over. I don’t like it.

Housewife: Same thing as communism.

College student: Exaggerated nationalism. The creation of artificial hatreds.

Housewife: A large Florida rattlesnake in summer.

Author: I can only answer in cuss words.

Housewife: The corporate state. Against women and workers.

Librarian: They overturn things.

Farmer: Lawlessness.

Italian hairdresser: A bunch, all together.

Elevator starter: I never heard of it.

Businessman: The equivalent of the ARA.

Stenographer: Terrorism, religious intolerance, bigotry.

Social worker: Government in the interest of the majority for the purpose of accomplishing things democracy cannot do.

Businessman: Egotism. One person thinks he can run everything.

Clerk: II Duce, Oneness. Ugh!

Clerk: Mussolini’s racket. All business not making money taken over by the state.

Secretary: Blackshirts. I don’t like it.

Author: A totalitarian state which does not pretend to aim at equalization of wealth.

Housewife: Oppression. No worse than communism.

Author: An all-powerful police force to hold up a decaying society.

Housewife: Dictatorship. President Roosevelt is a dictator, but he’s not a fascist.

Journalist: Undesired government of masses by a self-seeking, fanatical minority.

Clerk: Me, one and only, and a lot of blind sheep following.

Sculptor: Chauvinism made into a religious cult and the consequent suppression of other races and religions.

Artist: An attitude toward life which I hate as violently as anything I know. Why? Because it destroys everything in

life I value.

Lawyer: A group which does not believe in government interference, and will overthrow the government if necessary.

Journalist: A left-wing group prepared to use force.

Advertising man: A governmental form which regards the individual as the property of the state.

Further comment is really unnecessary. It is safe to say that kindred abstractions, such as “democracy,” “communism,””totalitarianism,” would show a like reaction. The persons interviewed showed a dislike of “fascism,” but there was little agreement as to what it meant. A number skipped the description level and jumped to the inference level, thus indicating that they did not know what they were disliking. Some specific referents were provided when Hitler and Mussolini were mentioned. The Italian hairdresser went back to the bundle of birch rods in imperial Rome.

There are at least fifteen distinguishable concepts in the answers quoted. The ideas of “dictatorship” and “repression” are in evidence but by no means uniform. It is easy to lump these answers in one’s mind because of a dangerous illusion of agreement. If one is opposed to fascism, he feels that because these answers indicate people also opposed, then all agree. Observe that the agreement, such as it is, is on the inference level, with little or no agreement on the objective level. The abstract phrases given are loose and hazy enough to fit our loose and hazy conceptions interchangeably. Notice also how readily a collection like this can be classified by abstract concepts; how neatly the pigeonholes hold answers tying fascism up with capitalism, with communism, with oppressive laws, or with lawlessness. Multiply the sample by ten million and picture if you can the aggregate mental chaos. Yet this is the word which is soberly treated as a definite thing by newspapers, authors, orators, statesmen, talkers, the world over.

Using such words as “fascism” without knowing what they mean, is an example of the linguistic habit of “psittacism.” Take a look at Walter Laqueur’s chapter “Foreign Policy and the English Language” in his America, Europe, and the Soviet Union, 1983.

Catch-22 Bullshit

So, “catch-22” is applicable to any self-defeating rule or situation. In the Wikipedia article, an example is given of trying to look for one’s lost eyeglasses. But to see your eyeglasses, you have to have eyeglasses, which you don’t have: catch-22.

What comes to my political mind are such matters as secessions. For example, Catalonia wanted to secede from Spain. To do so, by the Spanish Constitution, it needed a national referendum. And to have a national referendum, it needed a vote of Parliament, which was not forthcoming. It resorted to an “illegal” Catalonian referendum, which, in fact, favored secession. But the Spanish Supreme Court ruled this unconstitutional. So, for Catalonia to have a legal chance of secession, it would have to change the Constitution . . . a practical impossibility — hence, a catch-22 situation.

Generally, any radical change in politics, requires a change in the constitution. But constitutions are extremely hard to change. They are secured by catch-22 situations. Consider how difficult it is to amend the US Constitution.

The only country which has allowed relatively easy democratic changes to its Constitution is Switzerland through national initiatives and referendums. See Switzerland

Origins of the State — by Conquest

“A state is a compulsory political organization with a centralized government that maintains a monopoly on the legitimate use of force within a certain geographical territory.”

For my purposes, this definition will do. However, from my individual perspective, what is important to me and to everyone else, is the fact that we cannot occupy a piece of subsistence land for free, but must submit to the dictates of a centralized government.

How is the “State” different from a tribe, which also may prevent me from occupying a piece of land? Let us express the difference in the following way. If I am a member of a tribe, then I will be allowed to occupy a piece of land for free. But, if I am a member of a State, I will not be allowed to occupy a piece of land for free.

From this perspective, the question is: how is this transition from tribal free occupancy to a State non-free occupancy possible? This is the problem which has been labeled the problem of “primitive accumulation.”

One approach is to point out the differences in human natures. Some are gifted (i.e., intelligent, diligent, thrifty, etc.); others are not. OK, so the gifted will do better with their land holding than the less-gifted. Still, the less gifted will not work for the gifted unless their reward is equal or better than what they can accomplish on their own piece of land.

But the situation in a State is that many would be better off if they had access to free subsistence land; but they do not.

Despite the different theories of “State formation,”, only one is, for me, convincing. This is the conquest theory, which has been best formulated by Franz Oppenheimer in his book The State

I urge the reader to read the book. The author is clear, brief, reasonable, and convincing. I will only focus on what to me is the convincing, deductive argument for the conquest theory of the State.

He starts with the following assumption:

“No one will work for another if he can do as well or better by living off subsistence land. All teachers of natural law, etc., have unanimously declared that the differentiation into income- receiving classes and propertyless classes can only take place when all fertile lands have been occupied. For so long as man has ample opportunity to take up unoccupied land, "no one," says Turgot, "would think of entering the service of another"; we may add, "at least for wages, which are not apt to be higher than the earnings of an independent peasant working an unmortgaged and sufficiently large property"; while mortgaging is not possible as long as land is yet free for the working or taking, as free as air and water. Matter that is obtainable for the taking has no value that enables it to be pledged, since no one loans on things that can be had for nothing.

Let me formulate this as an explicit argument:

1. Person x will not work for person y, if x can do as well or better on his own.

2. x can do as well or better on his own, if he has free access to subsistence land

3. There are z acres of available fertile land in the world.

4. There are m number of people in the world

5. z/m = g

6. In order to subsist, x must have access to h acres of land

7. g > h

9. Therefore, there is enough subsistence land for each person

Oppenheimer gives us the statistics for available land in Germany as well as in the world, at the time when he wrote (1914); concluding that there is ample land for everyone. But despite this, we are prevented from taking free occupancy by States.

The rest of the book is a narrative of conquests of one group of people by another. I need no further convincing, since the history of man is a history of war and conquest.

I want to conclude with the observation that since Oppenheimer wrote, we have a massive increase in populations and a decrease in available subsistence land. When Oppenheimer wrote, he gave 1.8 billion as the number of people in the world, and estimated 181 billion acres of available land, which would give each person roughly 100 acres. We have now 7.7 billion people, which, if that same amount of land were available, would give each person about 23 acres, which is still sufficient for subsistence.

But the amount of land available for agriculture has dropped substantially . . .

Let me add the following:

“Private property in land has no justification except historically through power of the sword. In the beginning of feudal times, certain men had enough military strength to be able to force those whom they disliked not to live in a certain area. Those whom they chose to leave on the land became their serf’s, and were forced to work for them in return for the gracious permission to stay. In order to establish law in place of private force, it was necessary, in the main, to leave undisturbed the rights which had been acquired by the sword. The land became the property, of those who had conquered it, and the serfs were allowed to give rent instead of service. There is no justification for private property in land, except the historical necessity to conciliate turbulent robbers who would not otherwise have obeyed the law. This necessity arose in Europe many centuries ago, but in Africa the whole process is often quite recent. It is by this process, slightly disguised, that the Kimberley diamond mines and the Rand gold-mines were acquired in spite of prior native rights. It is a singular example of human inertia that men should have continued until now to endure the tyranny and extortion which a small minority are able to inflict by their possession of the land. No good to the community, of any sort or kind, results from the private ownership of land. If men were reasonable, they would decree that it should cease to-morrow, with no compensation beyond a moderate life income to the present holders.”

Bertrand Russell, Principles of Social Reconstruction, 1916,pp. 125-126.

Land and Liberty

I look at the history of the United States from the perspective of a person who is forced, in one way or another, to work for a living, as contrasted, for example, to an American Indian who could go anywhere and do anything he wanted. As Rousseau put it: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” Why is this so?

I see myself as a wage-slave. Because some may think I am exaggerating, let me explain. There is a broad sense of the term “slave” such that anyone who is forced to do anything by anyone else is a slave to that person. In this broad sense, children are normally slaves of their parents; wives are often slaves of their husbands; soldier are slaves to their superiors; worker are slaves to their employers; prostitutes are slaves to their pimps.

Slavery, in a narrow or technical sense, applies to the condition of people who are, in some sense, the property of some other person — with or without the possibility of gaining freedom. The severest form of this condition is chattel slavery in which the master is free to kill the slave.

Slavery is, then, a continuum of conditions, with degrees of restrictions, degrees of penalties, and degrees of freedoms.

In general, as I view it, slavery consists of being forced to do work for someone else. This forcing can be direct or indirect. In civilized societies, all forms of slavery are the results of laws.

Direct slavery occurs where the law stipulates that a particular person is the slave, serf, servant, laborer, or apprentice of another. Some laws allowed people to sell themselves into bondage. An example of this is the American Colonial practice of indentured servitude, whereby for the price of passage to America an immigrant sold himself into servitude for a period ranging from 2 to 7 years.

Indirect slavery occurs when the penalty for not working for someone else is a deprivation of the means for existence — a deprivation of access to subsistence land.

In the American colonies, it was unlawful to be a vagabond, i.e., a homeless person. Such people were arrested and made into laborers for someone or other. If no one could be found to take them, they were whipped and branded through the right ear. For a third offence, they were executed. As remnants of this policy, the United States still has vagrancy laws.

Direct slavery still exists in the United States in the form of military induction (when invoked). In such an event, a civilian is being forced to become a soldier. If he refuses, he will be imprisoned or, under some circumstances, executed. On the other hand, enlistment into the military is like indentured servitude — one makes an agreement with the government to serve a number of years (technically it is eight years), and the punishment for breaking such an agreement (with exceptions) is normally imprisonment.

Indirect slavery is the result of a deprivation of access to free subsistence land. The United States does not provide for free access to subsistence land, and in this manner forces everyone to get money for subsistence. Even if one manages to buy some land (or even get it for a nominal fee as was provided by the Homestead Act of 1862), one cannot simply subsist on it, because there are always state property taxes to be paid. And if these taxes are not paid, the land is confiscated by the state.

For this reason alone, it is proper to call the present economic and government system of the United States one of wage-slavery. The ultimate land owner is the government which collects property, sales, income, and other taxes as it sees fit.

In addition, because the government does have an enormous amount of money, it is also the largest employer and buyer. The bulk of its budget — about half a trillion dollars — is spent on military agents and tools of enforcement — airplanes, warships, tanks, bombs, missiles, bullets, and such. Often, the youth who are lured into the military are those who cannot afford to pay for education or job training. This is an “economic draft” which ensures that the United States government will have a steady supply of enforcers and canon fodder, drawn largely from the poor.

Capitalism, as I understand it, is the economic system which makes all land into a sellable and taxable commodity. It is a system which does not recognize an unalienable (unsellable) right to free land — though such a right is implict in the Declaration of Independence as the unalienable (unsellable) right to the pursuit of happiness. Happiness, in this instance, is nothing more than subsistence, and one cannot subsist in an independent and self-sufficient manner without access to land.

All major peasant uprisings and peasant revolutions have recognized the connection between liberty and free land. And this sentiment was expressed by peasants; not by landlords or merchants (bourgeoise). Landlords simply wanted to maintain possession of their lands, while merchants wanted to purchase land. It was to the advantage of peasants only to have access to free land.

The English, the American, and the French Revolutions were not peasant revolutions — they were revolutions of the aristocracy against a monarchy. Though there were many peasant and slave revolts throughout history, the first successful revolution of slaves was the Haitian Revolution of 1804. In the 20th century, the Mexican, the Russian, and the Spanish Revolutions are examples of three major peasant revolutions — and it is not surprising that their slogans were “Tierra y Libertad,” “Zemlya y Volya,” Land and Liberty.

The purpose of Political Liberty is to foster Economic Liberty. Political liberty is needed to get agreement for economic policies. And although the United States allows more political freedom than any other country, because of media control by corporations, it is extremely hard to get a political consensus about better economic policies. Right now, both domestically and internationally, the United States is against any policy which would give away land for free to anyone, without also making it a sellable commodity. Consequently, the following may be a true generalization of U.S. foreign policy: it is a suffecient reason for U.S. intervention in another country, if that country adopts an agrarian policy of giving away land for free. The underlying reason is that a country of self-sufficient and independent land owners will not yield a pool of cheap wage-slaves, including soldiers, for capitalists.

| “In former times the marauding minority of mankind, by means of physical violence, compelled the working majority to render feudal services, or reduced them to a state of slavery or serfdom, or at least made them pay a tribute. Nowadays the dependence of the working classes is secured in a less direct but equally efficacious manner, viz. by means of the superior power of capital; the labourer being forced, in order to get his subsistence, to place his labour power entirely at the disposal of the capitalist. So there is a semblance of liberty; but in reality the labourer is exploited and subjected, because, all the land having been appropriated, he cannot procure his subsistence directly from nature, and, goods being produced for the market and not for the producer’s own use, he cannot subsist without capital. Wages will rise above what is wanted for the necessaries of life, where the labourer is able to earn his subsistence on free land, which has not yet become private property. But wherever, in an old and totally occupied country, a body of labouring poor is employed in manufactures, the same law, which we see at work in the struggle for life throughout the organized world, will keep wages at the absolute minimum”

F. A. Lange, Die Arbeiterfrage. Ihre Bedeutung fur Gegenwart und Zukunft. Vierte Auflage. 1861, pp. 12, 13. Quoted by H. J. Nieboer, Slavery: As an Industrial System (Ethnological Researches), 2d edition, 1909, p. 421. |

Solution to the Unemployment Problem

A Free Land Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

Each person has a right to free and non-taxable subsistence land.

“. . . every man has, by the law of nature, a right to such a waste portion of the earth as is necessary for his subsistence.” Thomas More, Utopia

“Not the constitution, but free land, and its abundance of natural resources open to a fit people, made the democratic type of society in America for three centuries.” Frederick Turner, Chapter XI, The West and American Ideals, Frontier in American History.

| If a person has no access to land, then that person

If a person is unemployed and does not want to starve and does not want charity, then that person must live by criminal activity. |

“. . . overpopulation is critical today and may well make the distribution question moot tomorrow.” Paul and Anne Ehrlich, The Population Explosion (1990), p. 21. |

Top-Down or Bottom-Up Democracy?

Indirect democracy can be either in a bottom-up manner, by electing delegates from a small community of about 150; or in a top-down manner, by masses of people (of thousands or millions) electing representatives. [I call this Mass Democracy]

Most of the world practices [Mass] Representative Democracy, giving executive power to a single individual — be it a mayor, a governor, a monarch, a president, or a prime-minister (except for Switzerland, which places executive power in the hands of a council of seven individuals).

Below are two videos. The first explains some of the detrimental features of [Mass] Representative Democracy. [See also Peter Kropotkin’s “Representative Government” (1885)] The second is about the benefits of a bottom-up democracy.

Bullshit, Bullshitters, and Bull Sessions

To make these claims plausible, I have to clarify the concepts of “bullshit” and “bullshitter.”

Bullshit

Those who say “bullshit” do so in reaction to some utterance or group of utterances. Saying “bullshit” is a dysphemistic way of expressing a rejection. Only in this sense, is “bullshit” a unitary concept. But the things to which a rejection applies are varied. This requires a listing. The first thing that comes to mind is a determination that a claim is false. If we used a neutral expression, i.e., neither a euphemism nor a dysphemism, we would say “That is false.” But resorting to a dysphemism — for whatever reason — we say “That is bullshit.”

What I have written above indicates the pattern for various other rejections. So, to save space, all I need do is present a table with neutral rejections and equivalent dysphemistic rejections.

| Object of Rejection | Neutral Rejection | Dysphemistic Rejection |

| Statement | False | Bullshit |

| Statement or Group of Statements | Nonsensical or Meaningless | Bullshit |

| Subject of Discourse | Trivial or Unimportant | Bullshit |

| Argument | Invalid or Weak | Bullshit |

| Proposal | Impractical, Unworkable, Unrealistic | Bullshit |

| [Demand to do something | “No” | “Bullshit” |

Bullshitter

What all the writer on the nature of a bullshitter have missed is the identification of the bullshitter with Plato’s portrayal of a Sophist, and his contemporary embodiments in the lawyer, the politician, and the salesman. The essential trait of a bullshitter is not, as Frankfurt thinks, with a sloviness towards truth. but in the fact that he is more interested is winning or succeeding at whatever that he is trying to accomplish. And, the better he is at bullshitting, the more he is interested in knowing what the truth is. But his interest in the truth is not to express it, but to manipulate it to his advantage.

The goal of a lawyer is to win. He may take a case in which he is indifferent to the guilt or innocence of his client (an indifference to the truth), and his goal is for his client to prevail. Now, in his arsenal of techniques for winning, he may resort to using bullshit — meaning making false statement, pursuing a trivial matter, or using the panopoly of fallacies, such as ad hominem, red herring, appeal to emotions, etc. But if he is a sophisticated lawyer facing a sophisticated prosecutor, jury. and judge, then he may decide not to use bullshit of any kind. He will resort to various omissions of relevant material, and to selectively focus on issues to his advantage. Exactly the same strategy could be used by a politician and salesman. They are all bullshitters because they use language for the sake of winning (and not for gaining knowledge or finding the truth) — and depending on the context, they will resort to or refrain from using bullshit.

Bull Session

I think that Frankfurt is right in thinking of a bull session as a sort of explorations of hypotheses. This exploration can be done in a frivolous or a serious manner. Participant can pretend to hold particular views, and see what the reaction is. This can be done for sheer entertainment or to learn mind-sets of others. or whatnot. A bull session does not have to include any bullshitters or bullshit — though it may include both.