Take, for example, the label “fascism.” Stuart Chase, in his book, appropriately titled The Tyranny of Words, 1938, asked many people to tell him what “fascism” meant for them. Below is his take on “fascism,” and the result of his survey.

Pursuit of “fascism.” As a specific illustration, let us inquire into the term “fascism” from the semantic point of view. Ever since Mussolini popularized it soon after the World War, the word has been finding its way into conversations and printed matter, until now one can hardly go out to dinner, open a newspaper, turn on the radio, without encountering it. It is constantly employed as a weighty test for affairs in Spain, for affairs in Europe, for affairs all over the world. Sinclair Lewis tells us that it can happen here. His wife, Dorothy Thompson, never tires of drawing deadly parallels between European fascism and incipient fascism in America. If you call a professional communist a fascist, he turns pale with anger. If you call yourself a fascist, as does Lawrence Dennis, friends begin to avoid you as though you had the plague.

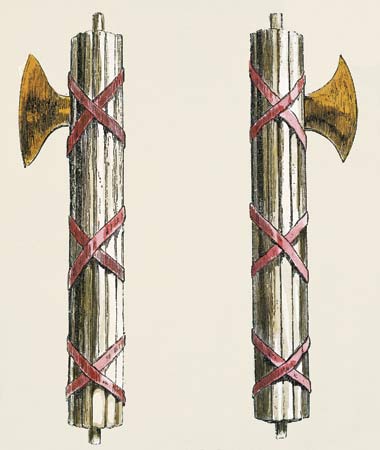

In ancient Rome, fasces were carried by lictors in imperial processions and ceremonies. They were bundles of birch rods, fastened together by a red strap, from which the head of an axe projected. The fasces were symbols of authority, first used by the Roman kings, then by the consuls, then by the emperors, A victorious general, saluted as “Imperator” by his soldiers, had his fasces crowned with laurel.

Mussolini picked up the word to symbolize the unity in a squad of his black-shirted followers. It was also helpful as propaganda to identify Italy in 1920 with the glories of imperial Rome. The programme of the early fascists was derived in part from the nationalist movement of 1910, and from syndicalism. The fascist squadrons fought the communist squadrons up and down Italy in a series of riots and disturbances, and vanquished them. Labour unions were broken up and crushed.

People outside of Italy who favoured labour unions, especially socialists, began to hate fascism. In due time Hitler appeared in Germany with his brand of National Socialism, but he too crushed labour unions, and so he was called a fascist. (Note the confusion caused by the appearance of Hitler’s “socialism” among the more orthodox brands.) By this time radicals had begun to label anyone they did not like as a fascist. I have been called a “social fascist” by the left press because I have ideas of my own. Meanwhile, if the test of fascism is breaking up labour unions, certain American communists should be presented with fasces crowned with laurel.

Well, what does “fascism” mean? Obviously the term by itself means nothing. In one context it has some meaning as a tag for Mussolini, his political party, and his activities in Italy. In another context it might be used as a tag for Hitler, his party, and his political activities in Germany. The two contexts are clearly not identical, and if they are to be used one ought to speak of the Italian and German varieties as facism1 and fascism2.

More important than trying to find meaning in a vague abstraction is an analysis of what people believe it means. Do they agree? Are they thinking about the same referent when they hear the term or use it? I collected nearly a hundred reactions from friends and chance acquaintances during the early summer cf 1937. I did not ask for a definition, but asked them to tell me what “fascism” meant to them, what kind of a picture came into their minds when they heard the term. Here are sample reactions:

Schoolteacher: A dictator suppressing all opposition.

Author: One-party government. “Outs” unrepresented.

Governess: Obtaining one’s desires by sacrifice of human lives.

Lawyer: A state where the individual has no rights, hope, or future.

College Student: Hitler and Mussolini.

United Stales senator: Deception, duplicity, and professing to do what one is not doing.

Schoolboy: War. Concentration camps. Bad treatment of workers. Something that’s got to be licked.

Lawyer: A coercive capitalistic state.

Teacher: A government where you can live comfortably if you never disagree with it.

Lawyer; I don’t know.

Musician: Empiricism, forced control, quackery.

Editor: Domination of big business hiding behind Hitler and Mussolini.

Short story writer: A form of government where socialism is used to perpetuate capitalism.

Housewife: Dictatorship by a man not always intelligent.

Taxi-driver: What Hitler’s trying to put over. I don’t like it.

Housewife: Same thing as communism.

College student: Exaggerated nationalism. The creation of artificial hatreds.

Housewife: A large Florida rattlesnake in summer.

Author: I can only answer in cuss words.

Housewife: The corporate state. Against women and workers.

Librarian: They overturn things.

Farmer: Lawlessness.

Italian hairdresser: A bunch, all together.

Elevator starter: I never heard of it.

Businessman: The equivalent of the ARA.

Stenographer: Terrorism, religious intolerance, bigotry.

Social worker: Government in the interest of the majority for the purpose of accomplishing things democracy cannot do.

Businessman: Egotism. One person thinks he can run everything.

Clerk: II Duce, Oneness. Ugh!

Clerk: Mussolini’s racket. All business not making money taken over by the state.

Secretary: Blackshirts. I don’t like it.

Author: A totalitarian state which does not pretend to aim at equalization of wealth.

Housewife: Oppression. No worse than communism.

Author: An all-powerful police force to hold up a decaying society.

Housewife: Dictatorship. President Roosevelt is a dictator, but he’s not a fascist.

Journalist: Undesired government of masses by a self-seeking, fanatical minority.

Clerk: Me, one and only, and a lot of blind sheep following.

Sculptor: Chauvinism made into a religious cult and the consequent suppression of other races and religions.

Artist: An attitude toward life which I hate as violently as anything I know. Why? Because it destroys everything in

life I value.

Lawyer: A group which does not believe in government interference, and will overthrow the government if necessary.

Journalist: A left-wing group prepared to use force.

Advertising man: A governmental form which regards the individual as the property of the state.

Further comment is really unnecessary. It is safe to say that kindred abstractions, such as “democracy,” “communism,””totalitarianism,” would show a like reaction. The persons interviewed showed a dislike of “fascism,” but there was little agreement as to what it meant. A number skipped the description level and jumped to the inference level, thus indicating that they did not know what they were disliking. Some specific referents were provided when Hitler and Mussolini were mentioned. The Italian hairdresser went back to the bundle of birch rods in imperial Rome.

There are at least fifteen distinguishable concepts in the answers quoted. The ideas of “dictatorship” and “repression” are in evidence but by no means uniform. It is easy to lump these answers in one’s mind because of a dangerous illusion of agreement. If one is opposed to fascism, he feels that because these answers indicate people also opposed, then all agree. Observe that the agreement, such as it is, is on the inference level, with little or no agreement on the objective level. The abstract phrases given are loose and hazy enough to fit our loose and hazy conceptions interchangeably. Notice also how readily a collection like this can be classified by abstract concepts; how neatly the pigeonholes hold answers tying fascism up with capitalism, with communism, with oppressive laws, or with lawlessness. Multiply the sample by ten million and picture if you can the aggregate mental chaos. Yet this is the word which is soberly treated as a definite thing by newspapers, authors, orators, statesmen, talkers, the world over.

Using such words as “fascism” without knowing what they mean, is an example of the linguistic habit of “psittacism.” Take a look at Walter Laqueur’s chapter “Foreign Policy and the English Language” in his America, Europe, and the Soviet Union, 1983.