In the United States, we take linguistic nationalism for granted — everyone speaks English. Those that do not are almost invisible. And assimilating people into the English language is an almost gentle “melting pot.”

Not so in other parts of the world which practice a deliberate, forced linguistic assimilation to the dominant State language.

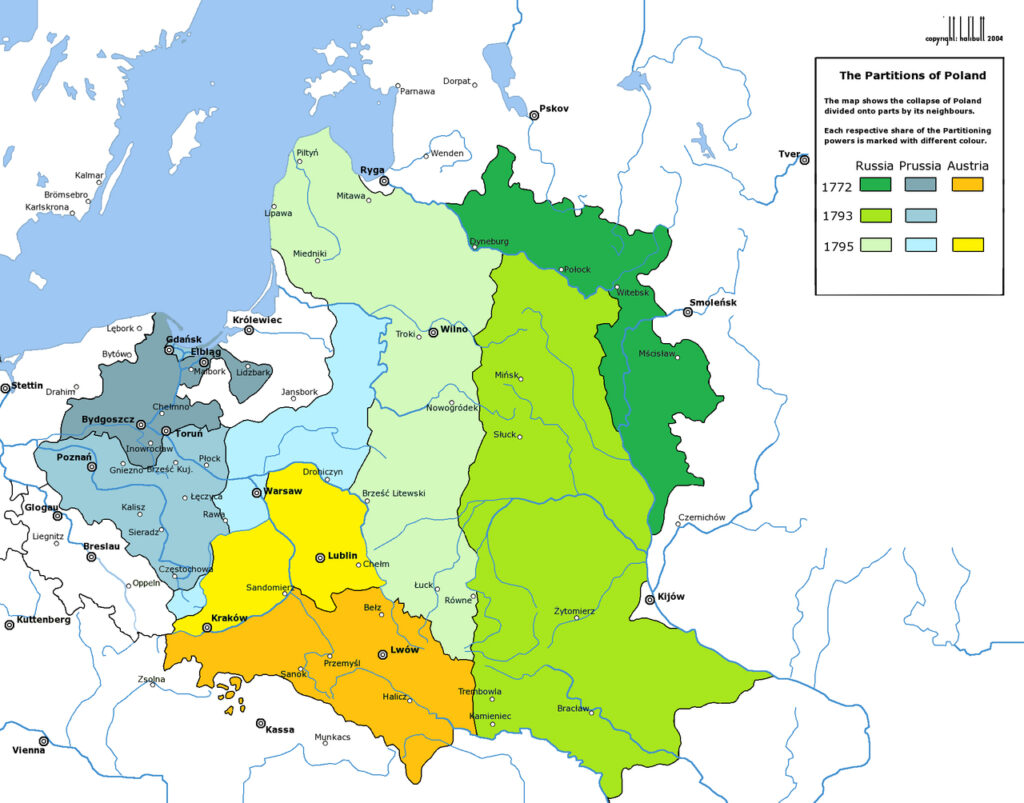

The plight between the current Kurds and pre-World War I Ukrainians is very similar. Not to go too far in history, the land of Ukrainians — i.e., those who speak the Ukrainian language — was in the 18th century divided between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as this map shows.

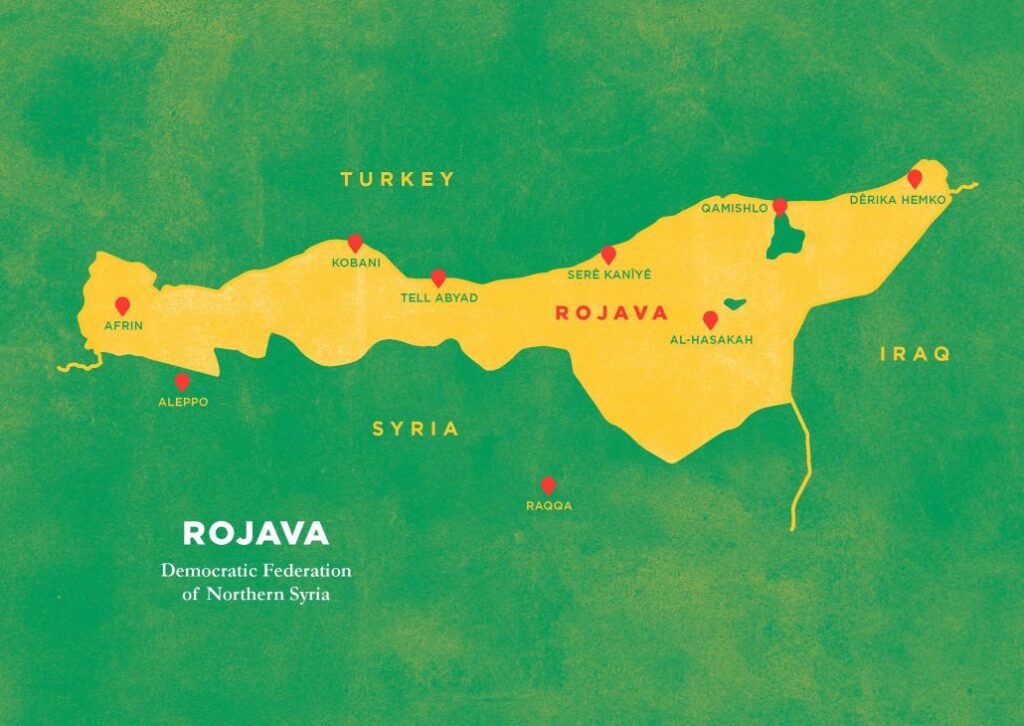

Similarly, the Kurds today find themselves living in four different States: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria (an area known as Kurdistan). And they are experiencing Turkification, Arabization, and Persianization.

In Ukraine, in the 1880s, Mykhailo Drahomanov, seeing no prospect for a Ukrainian State, and not desiring a centralized State, advocated an anarchist structure of federated communities, just as Ocalan is advocating today for the Kurds — and is succeeding in Rojava.

There is a difference between what I will call “State federalism” and a “federalism between communities.” What we have in the United States is a federation of States, and States themselves are federations of municipalities (which themselves have the structure of States). By a “State” I mean a centralized government with or without macro-democracy.

The leading Ukrainian intellectuals (including the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius) — and still into the period of the Russian revolution — which included the position of the first President of Ukraine, Hrushevsky — all favored “State federalism.” However, in view of the irreconcilability with the Bolshevik regime of the power structure, and the subsequent Russian invasion, the Central Council of Ukraine proclaimed Ukrainian independence as a sovereign State.

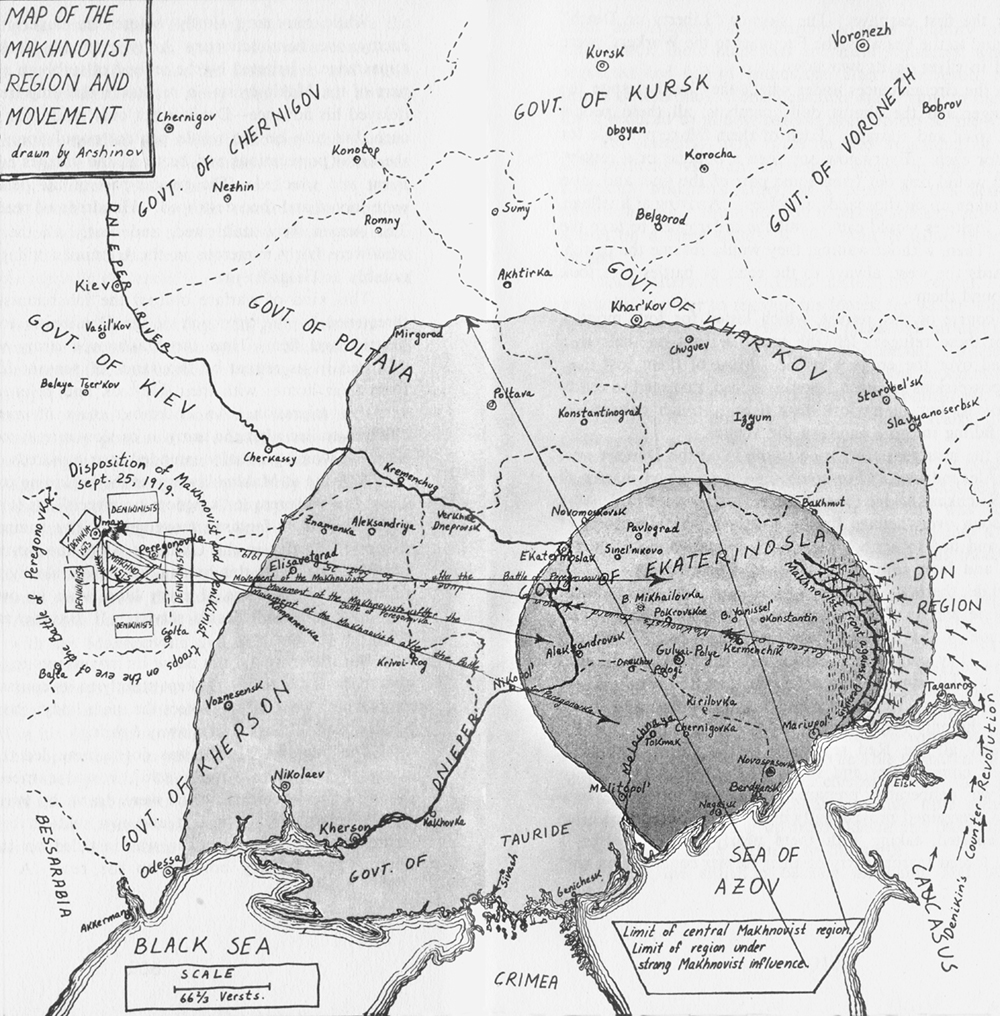

In the period of 1917-1921, Ukraine became a battleground between four forces: Ukrainian State nationalists, Russian and Ukrainian Bolsheviks, the reactionary White monarchists and republicans, and the Ukrainian anarchists, who wanted everyone of these centralizing invaders out of their territories. The most successful of these was Nestor Makhno, who although an anarchist and a follower of Peter Kropotkin, was not familiar with the writings of Drahomanov — though in fact he was in resonance with his thoughts. He managed to control a large region of southeastern Ukraine (see the map below).

After the First World War, Ukraine became a federated State within the Soviet Union suffering a genocide [Holodomor] under Stalin, and a policy of further Russification.

And after the downfall of the Soviet Union (1991), Ukraine remains a very centralized State with a sizable Russian-speaking population, some of whom have an evident desire to embrace mother Russia, a situation which made possible the Russian annexation of Crimea, and the present stalemate in the Donbass.