Several years ago in Chicago, I was called for jury duty. In the course of questioning potential jurors, the judge asked if anyone had any objections to finding the defendant guilty if the evidence showed him to be in violation of the law. Of all the potential jurors present, I was the only one who raised his hand. The judge then asked me to explain. I answered, “I would not find the defendant guilty if I believed the law to be unjust.” The judge responded: “Who are you to say whether the law is just or not.” I told the judge that I had used the word “believe.” That terminated his questioning of me, and he turned to the attorneys for any objections. They had none. By the way, I never got to be a juror because they picked their quota before reaching me.

I bring this up, because at the time I had no idea whether others had similar thoughts about juries and the law as I had. But in fact this stance is called “jury nullification.”

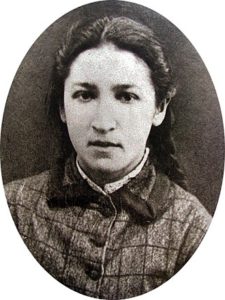

This reminds me of how a would-be assassin, Vera Zasulich, in 1878 in Russia, was acquitted by a sympathetic jury, despite the fact that she was guilty.