The common feature of all of them is that what transpired in these places was during civil wars. This means that the normal police powers of a State were either suspended or inoperative, and this created a period of time in which some other forms of organization could be tried. And if these experiments were to be experiments in anarchism, two things had to come into play — especially with peasants: redistribution of the land in some fair manner, and giving political power to a local community, such as, for example, a village. A third element operating in some of these circumstances, which may have acted as a catalyst, was a leader.

Let me consider each of these experiments in turn.

The Mexican Revolution. The beginning of the Mexican Revolution is taken to be November 20, 1910. It was started by Francisco Madero with his Plan of San Luis Potosi, which aimed to overthrown the then President of Mexico, Porfirio Diaz — which it did. [I am hesitant to call a coup — however orchestrated — a revolution. It is more like a non-democratic replacement of one “dictator” by another. This is also true of all the recent so-called “color” revolutions.]

What is of interest to me as an anarchist is the activity of Emiliano Zapata whose Plan of Ayala called for the restitution of land to the peasants of Morelos. This was one step towards anarchism. The other step would have been the formation of local autonomous communities. If Zapata had anything like this in mind, he wanted it to be implemented through a central government. And so, he pinned his hopes on a visionary President. In this respect, he was not an anarchist. But what is important is that there was a leader to whom the peasants flocked for the sake of land rights.

[Since 1994, there has been an anarchist movement in Mexico, in Chiapas. It calls itself the Zapatista Army of National Liberation.

Unlike the other anarchist movements which I focus on, it is taking place during a period in which Mexico is relatively stable.]

In Ukraine, during the Russian Revolution and Civil War (1917-1921), while various centralizing armies (Red, White, Nationalists) were aggresively expanding (through territorial incursions), Nestor Makhno, a self-conscious anarchist, and follower of Kropotkin, was engaged in two projects. The first was to fend off all military incursion into his territory. The second was to institute local councils for handling land distribution and self-organization. In both regards he was successful until overwhelmed by superior Bolshevik military strength.

In Spain there was a long-standing historical involvement with anarchism from the days of Bakunin. There was the CNT, a huge libertarian union, and there was the FAI, an anarchist federation. When Civil War broke out in 1936, in the anarchist areas, people collectivized farms and industry. Spain was an exception in not having one anarchist leader; instead it had an anarchist tradition. However, one anarchist fighter did stand out — Buenaventura Durruti, who was killed on Nov. 20, 1936.

The Spanish Republicans (including anarchists and communists) lost the Civil War to Franco who was aided both by Hitler and Mussolini.

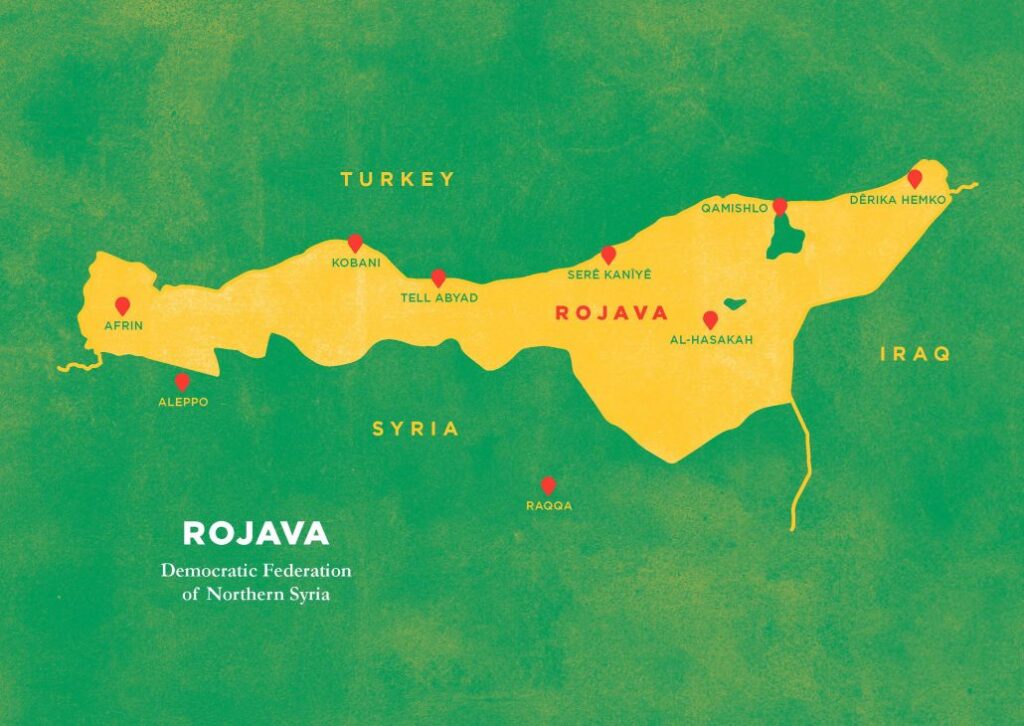

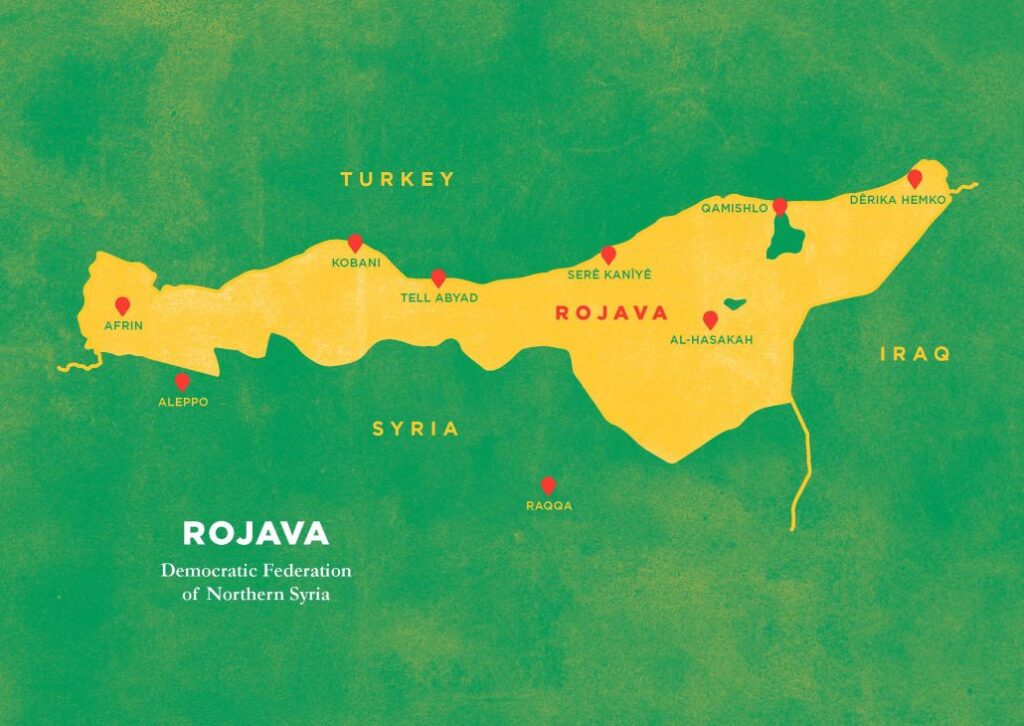

We come now to the present and the plight of the Kurds. After World War I, and despite Woodrow Wilson’s rhetoric about the self-determination of nationalities [Fourteen Points], the Kurds did not get a State; instead they are scattered within four States in the region known as Kurdistan.

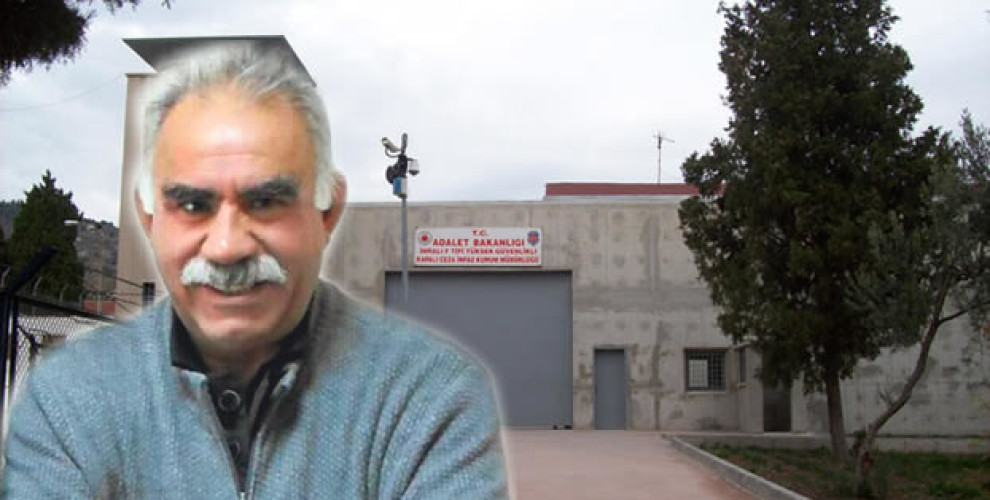

The Kurds are fortunate to have a leader, Abdullah Ocelan, who combines the features of the Ukrainian freedom and independence fighter Stepan Bandera and that of the anarchists Nestor Makhno and Mykhailo Drahomanov. Ocelan helped to found the PKK in 1978, a Marxist Kurdish worker’s party which waged guerrilla warfare against Turkey for an independent Kurdistan. This is analogous to Stepan Bandera as the head of the OUN-B fighting for Ukrainian independence. In 1999, Ocelan was abducted from Nairobi, Kenya and flow to Turkey, where he was tried, convicted, and sentence to be executed. This was commuted to life inprisonment on the island of Imrali on the Sea of Marmara.

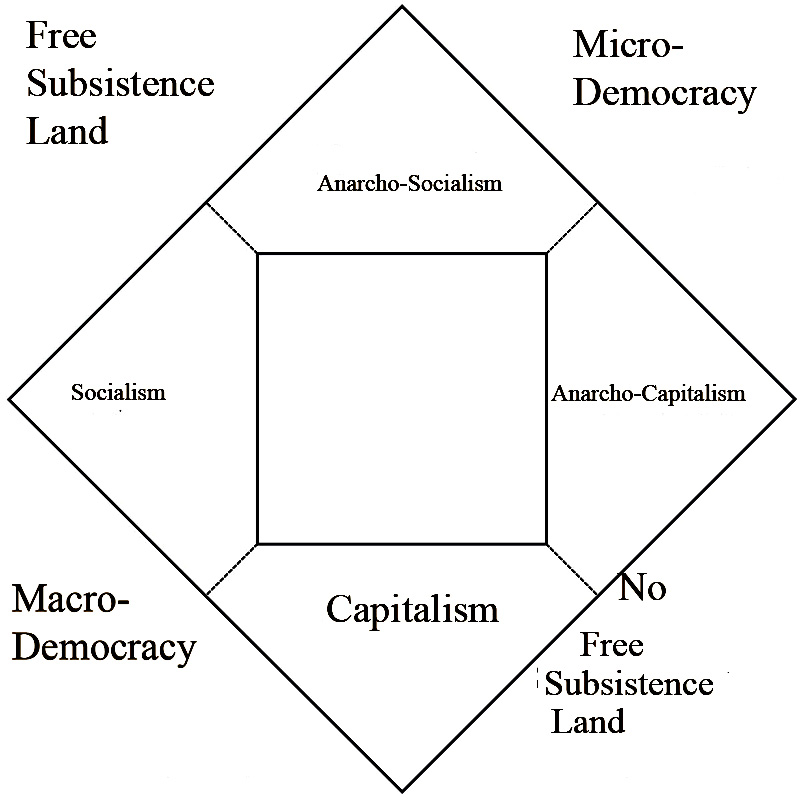

In 2005 Ocalan issues the Declaration of Democratic Confederalism in Kurdistan. This marked a break with his Marxism and an advocacy of anarchism, a position which was adopted by the PKK. His main inspiration came from Murray Bookchin‘s “The Ecology of Freedom [1982].”

[Ocalan’s current position is very similar to that which was advocated by Mykhailo Drahomanov, under similar circumstances when the Ukrainian population was living in territories ruled by Austro-Hungary in the west, and Russia in the east.]

So far since 2012, the Kurds in Syria have created a polyethnic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (Rojava) — an anarchist experiment. The hope is that all of Kurdistan can be made a part of federated States.

Whether Rojava and the hope of federalism will survive is yet to be seen.