An informal discussion. A bull session was originally a late-night college men’s dormitory conversation with a wide range of topics — politics, sex, sports, sex, religion, sex . . . The word “bull,” which meant something boastful or outlandish, came from — no surprise here — “bullshit.”

Why do I focus on the phenomenon of a bull session?

Because as I browse the internet to garner information, analyses, anticipations, and recommendations, I come across digital books, audio books, articles, and other visual and auditory media. I am also very attracted to lectures, speeches and interviews with prominent individuals. And since my interest is primarily political, I have come to appreciate the wisdom of such people as Chomsky, Hedges, Pilger, Kinzer, Sale, and others.

However, I am also curious to hear how a younger generation approaches political issues. And I have noticed that there are all these characters wearing headsets talking to other characters also wearing headsets. I think they are called political “podcasters,” as contrasted with the talk shows on television. And there are too many of them to even enumerate.

Since I consider myself in the anarcho-socialist spectrum, I tend to listen to would-be supporters and detractors within this spectrum.

A few years ago, I came across a young man, Cameron Watt, who made a number of videos about anarchism which were clearly and systematically presented at Libertarian Communist Platform. Here is one of his videos:

A Case for Revolution (2018)

By contrast to these clear and systematic expositions of libertarian socialism (aka anarchism), I came across a podcaster, Michael (Krechmer) Malice, who also calls himself an anarchist.

I tried very hard to understand the nature of his “anarchism” through the various podcasts which he does with others. But my endeavor to understand where he stands has so far been a failure.

So far, this is what I have learned. He is against a centralized State; and he is, as I am, for the right of secession. But when I try to find out a bit more by listening to his appearances on various podcasts, these podcasts turned into bull sessions. For example, in several podcasts when he was asked to characterize anarchism, he repeated that it is a matter of relating. He uses the phrase “you do not speak for me.” If paraphrased, it means that he requires getting an agreement from him on all matters.

On the Joe Rogan show, he proposed to substitute private security services for the police. But instead of pursuing the nature of anarchism further, the exchange with Joe Rogan turned into a gossip-like bull session.

On the Dave Rubin Report, he mentioned that he was a leftist against the State, and then the conversation turned to other things — more bull session.

In his podcast with Chris Williamson, confronted with the question: What Is The Hardest Question For Anarchism To Answer?, his answer was that he had no idea how to deal with parents who mistreat their children.

Also asked if there is anywhere an anarchistic territory, he answered that it is not a place but a relationship — i.e., of mutual agreement. But other then mentioning ancient Ireland, he could not mention any experiments with anarchism.

This makes me think that he is an anarcho-capitalist, because such a thing never existed, and, in my opinion, is an incoherent idea.

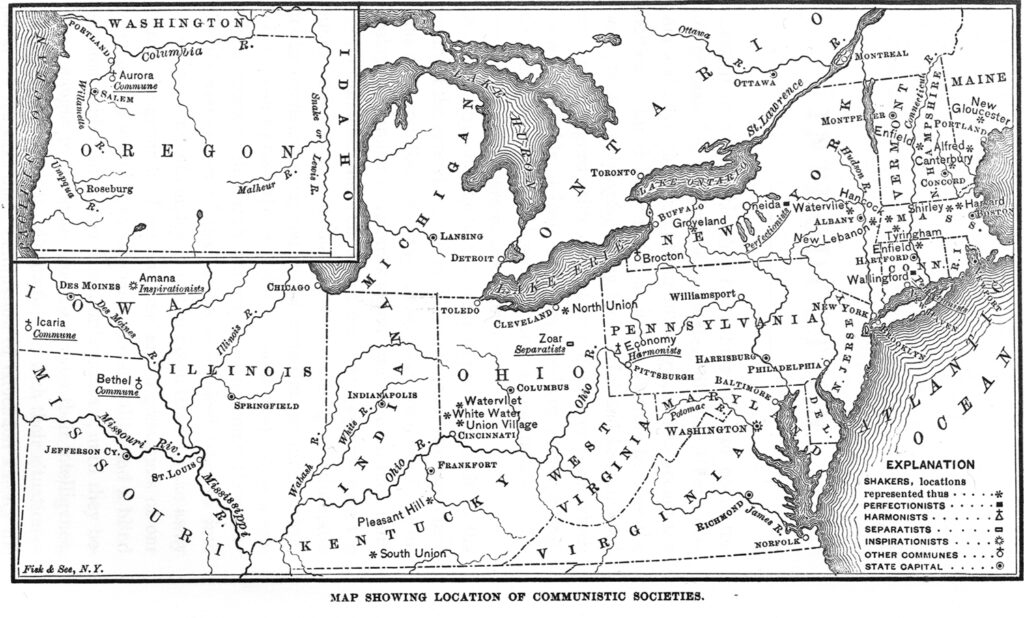

And, if he were an anarcho-socialist or an anarcho-communist, as Cameron Watt is, then he would have mentioned communism in primitive tribes, and anarchist communities which have escaped the State. And he could have mentioned the various communistic societies in the United States in the 19th century, he could also have mentioned Nestor Makhno and Makhnovchina in Ukraine (1918-1921), he could have mentioned the Spanish anarchism (1936-39), and today, the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico; Rojava in Syria, and the town of Cheran in Mexico.

But whatever his position is, it is smothered by the bull sessions of the podcasters.