Laura Flanders begins by citing the work of Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1851-2.

Andrew Chrucky

Laura Flanders begins by citing the work of Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1851-2.

Kirkpatrick Sale, Rebels against the future: the Luddites and their war on the Industrial Revolution: lessons for the computer age, 1996.

Below, an interview with Kirkpatrick Sale on his book (1996):

Below, an interview with Kirkpatrick Sale on his book, The Collapse of 2020 (2020):

As I was reading his account of Robert Owen (pp. 197-217), I came upon the following passage: “Perhaps those parts of his arguments which rest on general humanitarian considerations, rather than on logic-chopping discussions on Man’s will, make a stronger appeal to our generation, if only because here Owen is more universally human.” p. 208.

I want to reflect on this kind of criticism which is expressed by the phrase “logic-chopping” and its near synonym “nitpicking” or “quibbling.”This is criticism of something being done in excess of what is appropriate to the context. And a person who engages in excessive criticism is a “pedant.” And one who is oblivious to a need for any analysis at all and the need to make appropriate distinctions is a “philistine.” [I have put links for the meaning of these words.]

What is too much or too little depends on the context.

I personally have been constantly accused of “nitpicking” because I — almost invariably — ask: “What do you mean?” And I usually ask for the meaning of abstract words which have the suffix “-ism” (and for most political terms for parties and so-called “schools”), but also for the meaning of — what seem to me to be — names of fictions, like “God.”

I suppose the consequence of stirring up controversy in inappropriate contexts is being forced (in a metaphoric way of speaking) to drink hemlock.

Richard Wolff calls himself a Marxist. And though he doesn’t offer any definitions, he focuses on the phenomenon which he calls “exploitation.” And “exploitation” means that the employer gets a “profit” while the employee does not. There would be no “exploitation” if the employees shared equally in the “profit.” And he thinks this is possible only if the workers jointly owned the enterprise.

If this is “Marxism,” it is a severe truncation of what Marx wrote. Marx major work “Capitalism” is subtitled “A Critique of Capitalist Production.” It is, in the main, an economic analysis of how capitalistic businesses work, and why if they run unregulated (laissez-faire), they will self- destruct.

And although Wolff is right about capitalist “exploitation” and the fact that the employer reaps a profit, Wolff does not seem to concern himself with how this kind of “exploitation” is possible, even though under capitalism worker-owned enterprises are possible.

A fuller understanding of Marx, requires taking into account also how capitalistic mode of production is possible and how historically it came about. This is explained by Marx in the 8th part of Capital: “The So-Called Primitive Accumulation,” especially Chapter 26: “The Secret of Primitive Accumulation,” where it is written: “In actual history it is notorious that conquest, enslavement, robbery, murder, briefly force, play the great part.”

The simple truth is that by the conqueror’s law (which morphs into a centralized government) people are barred from a free access to subsistence land, and, following the period of the Black Death, there were instituted laws controlling employment and forbidding vagabondage, i.e., it was forbidden to be without work if you did not possess land. Sort of catch-22: you did not have to work for someone if you had land, but you couldn’t get land without working for someone. But even if you did have land, you had to pay rent or taxes, or both.

Marx believed that it was the technology which accounted for the various forms of production, and gave rise to different forms of political organizations (= the alleged thesis of historical materialism). But according to one critic, Rudolf Stammler in his Wirtschaft und Recht nach der materialistischen Geschichtsausffassung (1896), Marx inverted the reality: “the social relations of production cannot exist outside a definite system of legal rules.” [Karl Marx: Selected Writings in Sociology & Social Philosophy (1956), edited by T. B. Bottomore, in his “Introduction,” p. 33.]

My answer to Wolff striving for worker-controlled industries is that this can be achieved without resorting to a law such as that all factories are to be worker-controlled. If — by a different law — everyone is given a right to free subsistence land, then any entrepreneur will be able to secure workers only if he pays them something equivalent or better than they would get from working on their subsistence land. In other words, the worker would have better bargaining power resulting in a minimization or even a disappearance of profits.

Remember what Franz Oppenheimer wrote in, The State:

“For as long as man has ample opportunity to take up unoccupied land, “no one,” says Turgot, “would think of entering the service of another;” we may add, “at least for wages, which are not apt to be higher than the earnings of an independent peasant working an unmortgaged and sufficiently large property;” while mortgaging is not possible as long as land is yet free for the working or taking, as free as air and water.” p. 9-10

Why can’t I use that empty lot across the street? Because if I try, someone will complain to some government official and a policeman will come telling me that what I am doing is illegal, to stop and desist on the threat of arrest. And if I ignore him, he will arrest me. And I will be in a jail, where they will then feed me some vegetables and eggs, and even give me a chicken breast. In other words, they will give me (in exchange for a deprivation of my freedom to roam) the very things which I was trying to procure by my own efforts.

A bit paradoxical, don’t you think?

To explain this conundrum requires getting some knowledge of the culture of my vicinity. And as with all work — including the getting of information and knowledge — there is a division of labor. Knowledge is obtained by research and study, and the results are published in all sorts of places — mostly in scholarly journals and books. And these are stored, mostly in libraries, and now also on computers.

How does this relate to my problem of trying to understand why if I try to furnish my own food supply on the empty lot, I could wind up receiving food in jail, where I would rather not be?

How and where do I get an answer to this problem? If I go to a library, I am sure that someone there will figure out that this is a legal problem and point to the section housing the law books. And if I tell the librarian that I want a wider cultural and historical perspective, I will most likely be taken to a section on sociology and economics, and then to a section on history. And if I ask the librarian if there are any normative studies as to what should be the case, I will likely be taken to some section on political philosophy or political science (so-called).

You get the picture!

And if you pick up any of these “scholarly” writings, you will be bombarded with a nightmare of references and footnotes. Why? To prove to some decider (like an editor of some publication, or a chairman or a dean in some school who decides whether to hire the scholar), as well as to the reading public that the scholar did a whole lot of “research.”

So, what is literary “research”? It is the scrutiny of the work of others as to how they tried to solve some problem, and referencing the work of authors; so that others — if they so desire — can verify the references for accuracy and plausability of interpretation.

What would happen if we removed from a piece of scholarship all the footnotes and references?

The result would be some sort of alternative proposals for a solution. Let’s call the listing of proposed solutions — a librarian’s list.

But, although a listing of alternatives is good, what I really want is a solution — and if not a solution, at least the best alternative.

Now, I do not mean to single out the book by Alexander Gray, The Socialist Tradition: Moses to Lenin (1946), but it does serve as an example of what I want to stress. I have consulted it as a book about socialism, and have found the scholarship very helpful — I mean it is full of names, references, and footnotes — all very helpful for further research for a solution to my original problem.

It has led me to look at the work of Anton Menger and the uncovering of the early English writers on socialism, which present more alternatives.

However, the book also endeavors to provide us with the abstracted alternatives gleaned from all this scholarship, and to adjudicate between them.

Here, I believe, it fails. Not all the plausible alternatives are presented for consideration. There are too many conceptual blunders, and too many emotive disparagements.

In a broad sense of speaking, too much concentration on scholarship distracts and prolongs the finding of a solution to a problem, and is thus, in this sense, its enemy.

First, concerning the definition of “socialism,” Gray is all over the place talking about individualism, communism, justice, efficiency, equality — finally settling for an unsystematic classification of socialisms rather than for a definition. And even the classification is done on the basis of secondary matters.

Anton Menger, by contrast, at the very beginning of his book, sets up as his desiderata (criteria) for socialism three disjunctive conditions. By “disjunctive” I mean that any one of them singly is sufficient for socialism. And it is left as an open question whether the three are jointly compatible. The three are:

He quickly notes that the third is a species of the second. In other words, that labor is a way of getting subsistence.

In chapters 2-12 he goes over the literature on how these desiderata were treated, mostly the first. He spends much time considering how communities or associations were to be organized. This applies to colonies, as well as to domestic organizations. And in the last chapter 13, he offers possible solutions through a consideration of land ownership, which he lists as three possibilities:

Let me point out that this classification assumes that land is a sellable commodity, and that it can be owned either by individuals or groups. It does not include the possibility that land is not owned.

All three alternatives can exist in present States. It is simply which is preferable. The first alternative is what prevails in the world, dominated by private corporations. The existing laws allow private ownership, and the hiring of people for private production and private profit (or for whatever the owners wish).

He cites the Russian village (Mir) as an example of common ownership, and private use (the second alternative). Actually the Russian village did not “own” the land; it collectively managed the land, and through periodic democratic assemblies divided the arable land in some agreed to plots.

Proposals to nationalize the land are variations on this second alternative.

The third alternative was realized by the various communal colonies — either religious or non-sectarian — which, for example, were set up in the United States. He cites the reporting of William Hinds [American Communities] for these communitarian experiments.

His conclusion is that the socialist ideal is satisfied by these last two alternatives, but not having a clear proposal for how subsistence relates to labor, he simply notes that the right to subsistence prevails in these communitarian societies; thus, satisfying one socialist desideratum.

Critical commentary:

Although I disapprove of ad hominem arguments, here I offer an ad hominem circumstancial which should guide our critical consideration of Menger’s proposals. He, as a salaried professor of jurisprudence at the University of Vienna (and wanting to keep his job), should have kept away from a criticism of the State, and he did; simply mentioning that anarchists wish to eliminate the State. He himself was interested in how to lawfully realize socialism, i.e., in and by a State. And he did have Bismark’s social legislation as a model.

My first observation is this. All primitive tribes and stateless communities satisfy all three desiderata. But this is anarchism, which is not under Menger’s purview.

My second observation is this. The Russian Mir was owned by a landlord, and all of Russia was owned by a Czar, and both required taxes from the village. The village only determined land usage and how the taxes were to be distributed among the villagers.

My third observation is that all the communitarian colonies in the United States had to purchase the land either from the State or from individuals. In some cases, these colonies did so by borrowing money, which they had to pay back with interest. And let us not forget property taxes exacted by the individual states. Thus, although all colonies became self-sufficient concerning subsistence, they were forced to enter an outside market economy to repay their debts.

Strictly speaking, the first — and main — ideal of socialism cannot be fully realized by any of these alternative property holdings, as long as there is a State which takes taxes.

The other consideration, pointed out by Menger, is that the communitarian colonies — taken as individuals — were in competition with other corporations and individuals for a market. And success was not guaranteed. [This criticism applies to Richard Wolff’s proposal for worker-owned enterprises. And it does not solve the problem of unemployment and homelessness.]

Although I am interested in what these communitarians believed and how they managed their affairs, I am more focused on the fact that they had to purchase their land holdings, and that they had to pay property taxes.

I think there is a preconception in people’s mind about the vast amount of land which was open to settlement in “the frontier.” Well, let’s be clear, in areas where either a British colony, or eventually a State made a survey and gained control, i.e., jurisdiction, no land was available for free. Yes, those who ventured into the frontier beyond government control could eke out a living by hunting and gathering, and even by building a homestead, i.e., by squatting. But beside the danger of encroaching on Indian territory, as soon as the government reached their territory, these squatters had to pay for the land through what were called “preemption laws.” This means that they had the first right to buy the land. If they could not, they were evicted.

I found the book by Roy M. Robbins, Our Landed Heritage: The Public Domain 1776-1936, an eye opener. This book should be read in conjunction with Richard Morris, Government and Labor in Early America.

All land was the property of the State, and in May 20, 1785 (modified in 1787) a law was established that land was to be surveyed into Townships, an area of 6 x 6 miles, divided into 36 “sections” of 1 x 1 mile (640 acres). [As an aside. Under the Homestead Act of 1862, pioneers were granted 1/4 section (160 acres) (for a small processing fee and a condition that the land be “improved” within 5 years), and in 1865 General Sherman proposed to give 40 acres to former slaves — a proposal which was rescinded by President Johnson]

Land was to be sold at auction with a minimum of $1 per acre, and a $36 fee for the surveyed Township. (I have not determined what was the minimal acres which were sold, but apparently speculators gobbled up the land in huge chunks, which they then sold at retail inflated prices. And there were shady acquisitions galore.

My point is that prior to 1862 there never was land to be taken legally for free.

Next, let me make some other observations. Menger says that the first desideratum has implications of a negative sort. He claims that it implies that no one is allowed to rent out land, and that there is to be no interest taken on loans. I am not sure how universal he means to make these prescriptions. Given that farmers and manufacturers had to purchase land and machinery, there were various proposed schemes to set up Banks and Credit Unions which would take only a minimal interest to offset the cost of processing a loan.

I want to end with the following observation as found in Franz Oppenheimer’s book, The State:

“For as long as man has ample opportunity to take up unoccupied land, “no one,” says Turgot, “would think of entering the service of another;” we may add, “at least for wages, which are not apt to be higher than the earnings of an independent peasant working an unmortgaged and sufficiently large property;” while mortgaging is not possible as long as land is yet free for the working or taking, as free as air and water.” p. 9-10

Commentary:

After I perused Ruth Kinna’s Anarchism: A Beginner’s Guide (2005), it struck me that it was not for beginners, but a compendium for scholars of anarchism. For beginners, it should be short and to the point, and not be cluttered with names and classifications.

Given that there is an ordinary common usage for the words “anarchy,” “anarchist,” and “anarchism,” as meaning something chaotic and disorderly, there is a need to stipulate how one wishes to use these words in a laudatory rather than in a disparaging way.

There is also the problem that though anyone may call himself an “anarchist,” — or anything else he wishes — he may not be an “anarchist” in the stipulated sense.

There is also the problem caused by associating a description of a person, on the one hand, and the person’s actions, on the other, where the description has no relevance to the action. I have in mind, for example, Jordan Peterson calling Stalin a Marxist, and then blaming Stalin’s mass murders on Marxism. There would be some rationale for this if the doctrine of Marxism indeed called for mass murder. But it does not. Think of it this way. Assume that Marxism stipulates some end state, and is silent about the means. Then means are optional, rather than stipulated by Marxism. So, at best, we could say that Stalin used mass murder for Marxist ends.

In like manner, there were people who identified themselves as anarchists, and assassinated politicians. Here we have to distinguish again the state of affairs which one is aiming at (the ends), and the means which will bring this state about.

I call myself an anarcho-socialist for the following reason. I agree with Anton Menger that socialism ultimately aims at subsistence through the right to the full produce of one’s labor, which (in my view) can be obtained by having free access to land. On the other hand, I believe that what prevents this state of affairs from occurring is the State. Thus, for me, getting rid of the State is the essence of anarchism. And it seems to me to be a truncated reason for getting rid of the State simply because one does not like to take orders and be bossed around (as a slave, a serf, or a wage-laborer). No, I want to get rid of the State because in addition to bossing me around, it makes the obtaining of subsistence either more difficult than otherwise, or it blocks me from getting subsistence altogether.

My models for such an anarcho-socialistic existence are stateless, indigenous societies of people, who are called “primitive,” “savages,” and “barbarians.” And they are models, as are all models, in certain respects only. And they are models in two respects: they have a (1) free access to subsistence land, and are organized as (2) small democratic tribes.

Any other characteristics about such tribes are irrelevant; specifically, what is irrelevant are their beliefs, their economies, and their mores.

Ruth Kinna has a chapter about strategies to achieve an anarchist society. This is a separate problem and does not define anarchism. Some so-called anarchists believed that assassination of politicians is the way to go, others have believed in a general (universal) strike by workers. Others, like Nestor Makhno, used guerrilla warfare to defend themselves from aggressors. But the means for getting or defending an anarchist society are separate issues from the question of what constitutes an anarchist society.

Zorba the Greek reminds me of Nietzsche’s distinction in ancient Greek drama between the Apollonian and Dionysian traits of man. [See: Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy] Bates, playing the English gentleman, is full of conventional habits and beliefs which inhibit his emotional life; whereas Quinn, who plays the role of the vagabond Zorba, is in touch with his somewhat uninhibited emotions. What I got from the film is the need to unite — so to say — the head with the heart.

Seven Samurai is about a peasant village in Japan which is yearly assaulted by a band of horsed bandits who extort from the village most of its food supply, leaving them in a miserable condition. The villagers decide to obtain a defense against these yearly intruders by soliciting the help of seven samurai. The result is that in the ensuing defense most of the samurai are killed, but the village is saved. What I got from the film is the crucial need of weapons to defend oneself from enemies.

I value Apocalypto not for any didactic message as for a realistic depiction of historical and cultural realities. First, it depicts the life of hunter/gatherers as happy and fulfilling. To use Marshall Sahlins’ phrase, it depicts an “affluent society.” Second, it depicts the fact that other tribes took slaves; which is how African slaves were obtained by Europeans. Third, it shows a harsh contrast between the life of hunter/gatherers and the life of the inhabitants of the city, who are depicted as crowded, filthy, obedient, and poor. Fourth, the movie depicts the consequences of superstition: human sacrifice.

A Man for All Seasons is about St. Thomas More who used evasion rather than saying something false to escape being killed. But when he was given no option but to tell the truth, he did so at the cost of his life. Together, these movies show the realities of human nature and of life.

I remember the incident which revolutionized my thinking about the computer. It was sometime in the 1980ies when I was talking to a secretary at Keystone Junior College in Pennsylvania. I complained to her that I was working on a dissertation and had cut up my typed pages into various snippets and was assembling them all across the floor for rearrangement. In response she went to a huge computer and proceded to “cut and paste” written material on a screen. Wow!

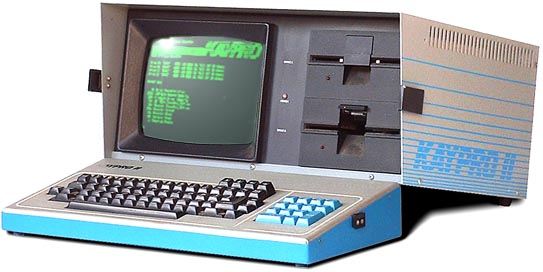

Shortly after, I browsed through a book on the Basic programming language, and immediately the similarity to symbolic logic hit me. Shortly after this — I think it may have been 1984 that I bought my first computer, a Kaypro, with two disc drives : one for the operating system (CP/M) and the other for data.

| Kaypro II | |

| Released: | 1982 |

| Price: | US $1595. |

| Weight: | 26 lbs |

| CPU: | Zilog Z80, 2.5 MHz |

| RAM: | 64K |

| Display: | 9″ green phosphor screen. 24 X 80 text only |

| Ports: | Serial port Parallel port |

| Storage: | Two internal 5-1/4″ SS-DD 195K drives |

| OS: | CP/M, SBASIC |

Soon I learned that there was a competitor operating system (DOS) on IBM computers, and a whole row of IBM clones was on the market. And the Kaypro company abandoned CP/M and went over to DOS.

I witnesses the emergence of the internet with a browser called Lynx (text-only), with which I learned to access a library catalog. Wow!

And then I bought an IBM clone which ran Windows 3.1, and soon came a browser from Cornell called Cello which introduces images. Wow!

Then came the web browser Mosaic in 1993 (with sound?), and the Web sprouted for me, followed by the brower Netscape, AOL, and the Internet Explorer — and here we are.

In 1990 I received my Ph.D. degree in Philosophy from Fordham University in Bronx, NY. One remark of one of the philosophers on the defense committee made a deep impression on me. He said something like this: “Too bad that such a fine dissertation will sit in the bookshelves picking up dust.”

I don’t remember the date, but I noticed that a graduate student at the University of Chicago was given space on the university’s computers for philosophical projects. I contacted him and received some space which I turned into a Wilfrid Sellars site. Soon however I purchased the domain “ditext.com” (url search reports 1998 as the year of registration) and transferred the material to this domain, giving my main web page the title “Digital Text International.”

Seeing the international reach of the internet, my ambition was to make everything about Sellars available, refusing to let my dissertation and other works “pick up dust on a library shelf.” And I was inspired to do other projects — like the Meta-Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

However, my sort of endeavor to make literature available on the internet has totally been superseded by such depositories as Wikipedia, Gutenberg, Archive.org

Since moving to Chicago in 1999, and discovering anarchism (which was never mentioned in any of my courses — ever), I have become an advocate of anarchism. And since bibliographies on anarchism, Switzerland, secession, and land rights are not sufficient to inspire readers, I decided a couple of years ago to do a Blog, in which I propagate my views. You see, while teaching introductory courses in philosophy at Wright College, Chicago, I came to realize from all my informal writings that I have ever done that my concern — private and philosophical — has always been to escape from bullshit.