I am interested primarily in understanding how our social world operates. By “social” I mean how humans interact with one another. And to do this I will rely on the vocabulary and explanations used by Franz Oppenheimer in his book

The State (which is part of the second volume of his four volume

Systems of Sociology [never completely translated into English]).

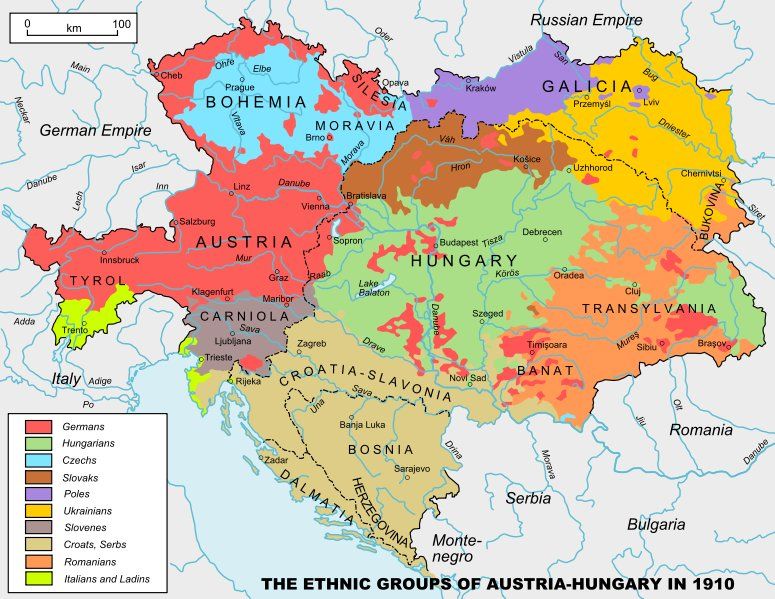

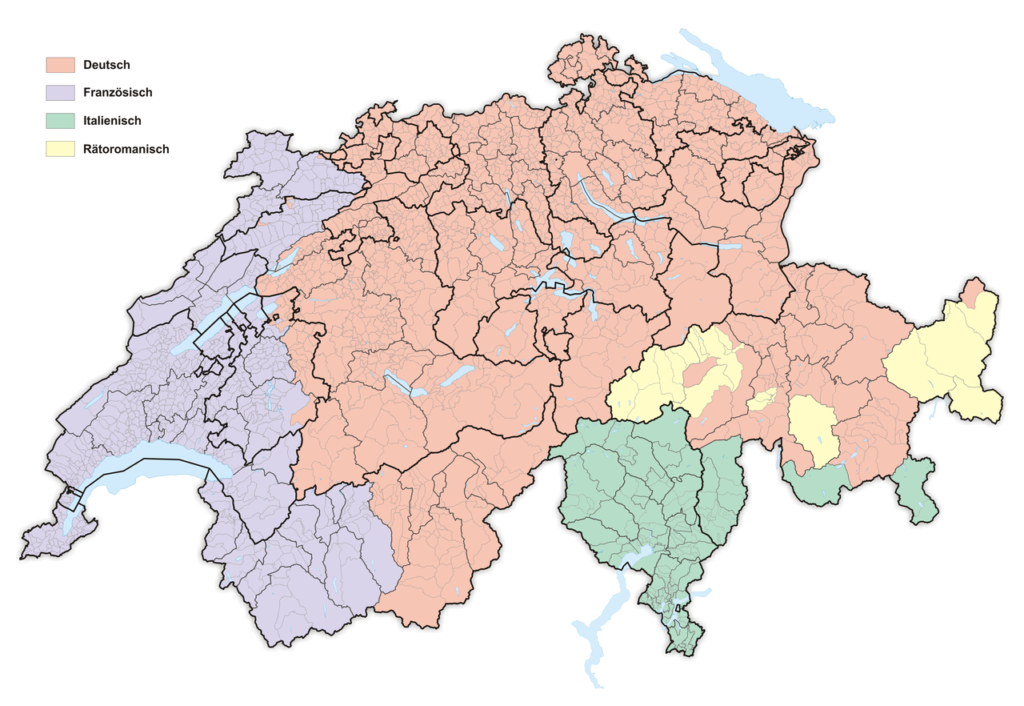

In the past (19th century) there was a constant concern with “the Social Problem.” Although this problem was seen from a symptomatic perspective as poverty, I think this problem can be expresses fundamentally and succinctly in the following way: some people by force prevent other people from taking up and occupying subsistence land. Put thus, all this means pre-historically is that groups of people delimited a territory as their property. This results in a scattering of tribes. Anthropologists study such “stateless people” especially indigenous people which were referred to as “savages” and “barbarians”, as contrasted with “civilized people.” The vocabulary comes from Lewis Morgan’s, Ancient Society (1877), which distinguished people by their tools, and “civilized people” by having a written script.

Now, because, as Oppenheimer calculated, there is and was enough land to go around. The prevention of someone taking up subsistence land can occur only by force. Presently this force is exercised by governments in States.

Oppenheimer believed that such governments and States can occur only by conquest of one external group by another. Some anthropologists quibble about this, contending that States can be formed through internal class divisions. Without entering into this quibble, let me offer the following two claims:

1. a sufficient condition for the formation of States is conquest by an external group.

2. the empirical data in recorded history is of warfare, strife, protest, rebellion, and conquest.

Moreover, these violences are almost invariably associated with particular individuals who are called emperors, kings, princes, rulers, conquerors, presidents, prime ministers, chancellors, and such. It is the deeds of these individuals which constitutes the history of States.

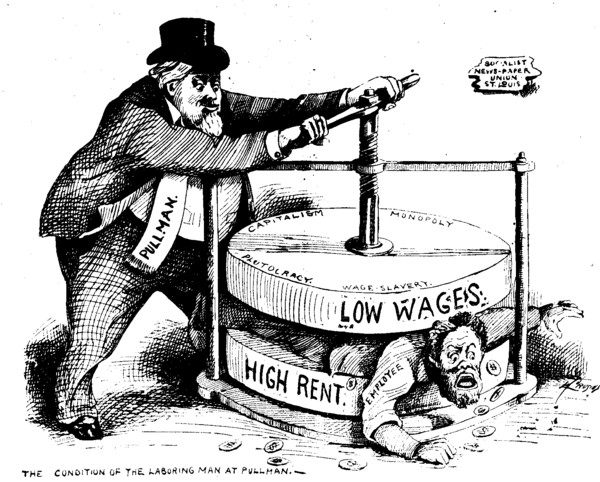

The Social Problem of forceful barring people from a free use of subsistence land is called by Oppenheimer the “political means” as contrasted with a free exchange of goods and services called by him the “economic means.”

Oppenheimer contrasted two ways of getting “honey.” (Honey is his metaphor for economic subsistence.) One is the method of the bear: attack the hive regardless of what happens to the bees and take the honey. The other method is that of the bee-keeper: take some honey, but leave enough so that the bees thrive and produce more honey for further taking.

Oppenheimer distinguished six stages (or ways) of how conquerors deal with the conquered people. The first stage in like that of the bear: kill the people and take the loot. This is illustrated in the Bible as the extermination of the Canaanites by Israelites, early Viking raids and pillages, and generally historic and modern ethnic cleansings and genocides. The second and subsequent stages or ways is that of the bee-keeper: make the conquered people slaves, or demand tribute, or settle among them as in feudalism and require goods and services, and later also payments (taxes), or just fees, licenses, and taxes. The so-called constitutional states attempt to give this class division legitimacy through such myths as the will of the people or a social contract, and finally as mass democracy (where thousands and millions vote for so-called “representatives”).

The essence of capitalism — which predated industrialization — is the continued barring of people from a free access to subsistence land. And since all the earth is now divided into States, the only places to go in order to escape a State are: a war zone, border lands, a frontier, mountains, swamps and jungles — where pursuit is difficult or unprofitable.