Carlson’s retort is typical of people who are put in a corner with no reasonable response.

Where on Paul Graham’s hierarchy of disagreement pyramid does Carlson’s reply belong?

Andrew Chrucky

Carlson’s retort is typical of people who are put in a corner with no reasonable response.

Where on Paul Graham’s hierarchy of disagreement pyramid does Carlson’s reply belong?

In the first video below is the discussion at Davos in which Bregman made his points.

In the second video, The Young Turks (TYT) comment on the exchange between Tucker Carlson and Rutger Bregman. Carlson invited Bregman to talk about the phenomenon of tax avoidance . . . but it never got there. Instead, Bregman focused on the problem of why such an issue as tax avoidance is not discussed by the major media, and his own answer was it is because billionaires pay millionaires — like Tucker Carlson — not to discuss it. At that point Carlson lost his composure with an emotive reaction of “go fuck yourself!”

The third video is the full exchange between Carlson and Bregman.

Video 1:

Video 2:

Video 3:

In the following clip, Noam Chomsky made the same charge against an interviewer as did Bregman against Carlson.

Take, for example, the label “fascism.” Stuart Chase, in his book, appropriately titled The Tyranny of Words, 1938, asked many people to tell him what “fascism” meant for them. Below is his take on “fascism,” and the result of his survey.

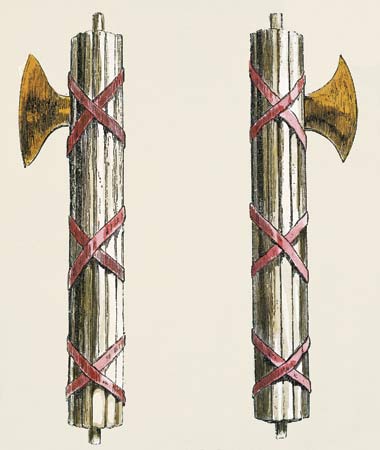

In ancient Rome, fasces were carried by lictors in imperial processions and ceremonies. They were bundles of birch rods, fastened together by a red strap, from which the head of an axe projected. The fasces were symbols of authority, first used by the Roman kings, then by the consuls, then by the emperors, A victorious general, saluted as “Imperator” by his soldiers, had his fasces crowned with laurel.

Mussolini picked up the word to symbolize the unity in a squad of his black-shirted followers. It was also helpful as propaganda to identify Italy in 1920 with the glories of imperial Rome. The programme of the early fascists was derived in part from the nationalist movement of 1910, and from syndicalism. The fascist squadrons fought the communist squadrons up and down Italy in a series of riots and disturbances, and vanquished them. Labour unions were broken up and crushed.

People outside of Italy who favoured labour unions, especially socialists, began to hate fascism. In due time Hitler appeared in Germany with his brand of National Socialism, but he too crushed labour unions, and so he was called a fascist. (Note the confusion caused by the appearance of Hitler’s “socialism” among the more orthodox brands.) By this time radicals had begun to label anyone they did not like as a fascist. I have been called a “social fascist” by the left press because I have ideas of my own. Meanwhile, if the test of fascism is breaking up labour unions, certain American communists should be presented with fasces crowned with laurel.

Well, what does “fascism” mean? Obviously the term by itself means nothing. In one context it has some meaning as a tag for Mussolini, his political party, and his activities in Italy. In another context it might be used as a tag for Hitler, his party, and his political activities in Germany. The two contexts are clearly not identical, and if they are to be used one ought to speak of the Italian and German varieties as facism1 and fascism2.

More important than trying to find meaning in a vague abstraction is an analysis of what people believe it means. Do they agree? Are they thinking about the same referent when they hear the term or use it? I collected nearly a hundred reactions from friends and chance acquaintances during the early summer cf 1937. I did not ask for a definition, but asked them to tell me what “fascism” meant to them, what kind of a picture came into their minds when they heard the term. Here are sample reactions:

Schoolteacher: A dictator suppressing all opposition.

Author: One-party government. “Outs” unrepresented.

Governess: Obtaining one’s desires by sacrifice of human lives.

Lawyer: A state where the individual has no rights, hope, or future.

College Student: Hitler and Mussolini.

United Stales senator: Deception, duplicity, and professing to do what one is not doing.

Schoolboy: War. Concentration camps. Bad treatment of workers. Something that’s got to be licked.

Lawyer: A coercive capitalistic state.

Teacher: A government where you can live comfortably if you never disagree with it.

Lawyer; I don’t know.

Musician: Empiricism, forced control, quackery.

Editor: Domination of big business hiding behind Hitler and Mussolini.

Short story writer: A form of government where socialism is used to perpetuate capitalism.

Housewife: Dictatorship by a man not always intelligent.

Taxi-driver: What Hitler’s trying to put over. I don’t like it.

Housewife: Same thing as communism.

College student: Exaggerated nationalism. The creation of artificial hatreds.

Housewife: A large Florida rattlesnake in summer.

Author: I can only answer in cuss words.

Housewife: The corporate state. Against women and workers.

Librarian: They overturn things.

Farmer: Lawlessness.

Italian hairdresser: A bunch, all together.

Elevator starter: I never heard of it.

Businessman: The equivalent of the ARA.

Stenographer: Terrorism, religious intolerance, bigotry.

Social worker: Government in the interest of the majority for the purpose of accomplishing things democracy cannot do.

Businessman: Egotism. One person thinks he can run everything.

Clerk: II Duce, Oneness. Ugh!

Clerk: Mussolini’s racket. All business not making money taken over by the state.

Secretary: Blackshirts. I don’t like it.

Author: A totalitarian state which does not pretend to aim at equalization of wealth.

Housewife: Oppression. No worse than communism.

Author: An all-powerful police force to hold up a decaying society.

Housewife: Dictatorship. President Roosevelt is a dictator, but he’s not a fascist.

Journalist: Undesired government of masses by a self-seeking, fanatical minority.

Clerk: Me, one and only, and a lot of blind sheep following.

Sculptor: Chauvinism made into a religious cult and the consequent suppression of other races and religions.

Artist: An attitude toward life which I hate as violently as anything I know. Why? Because it destroys everything in

life I value.

Lawyer: A group which does not believe in government interference, and will overthrow the government if necessary.

Journalist: A left-wing group prepared to use force.

Advertising man: A governmental form which regards the individual as the property of the state.

Further comment is really unnecessary. It is safe to say that kindred abstractions, such as “democracy,” “communism,””totalitarianism,” would show a like reaction. The persons interviewed showed a dislike of “fascism,” but there was little agreement as to what it meant. A number skipped the description level and jumped to the inference level, thus indicating that they did not know what they were disliking. Some specific referents were provided when Hitler and Mussolini were mentioned. The Italian hairdresser went back to the bundle of birch rods in imperial Rome.

There are at least fifteen distinguishable concepts in the answers quoted. The ideas of “dictatorship” and “repression” are in evidence but by no means uniform. It is easy to lump these answers in one’s mind because of a dangerous illusion of agreement. If one is opposed to fascism, he feels that because these answers indicate people also opposed, then all agree. Observe that the agreement, such as it is, is on the inference level, with little or no agreement on the objective level. The abstract phrases given are loose and hazy enough to fit our loose and hazy conceptions interchangeably. Notice also how readily a collection like this can be classified by abstract concepts; how neatly the pigeonholes hold answers tying fascism up with capitalism, with communism, with oppressive laws, or with lawlessness. Multiply the sample by ten million and picture if you can the aggregate mental chaos. Yet this is the word which is soberly treated as a definite thing by newspapers, authors, orators, statesmen, talkers, the world over.

Footnotes were written by Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel, the editors.

The following excerpt appears on pp. 227-8 of Chapter Seven: Intellectuals and Social Change

. . .

WOMAN: Noam, apart from the idea of the “vanguard,” I’m interested why you’re so critical of the whole broader category of Marxist analysis in general-like people in the universities and so on who refer to themselves as “Marxists.” I’ve noticed you’re never very happy with it.

CHOMSKY: Well, I guess one thing that’s unattractive to me about “Marxism” is the very idea that there is such a thing. It’s a rather striking fact that you don’t find things like “Marxism” in the sciences — like, there isn’t any part of physics which is “Einsteinianism,” let’s say, or “Planckianism” or something like that. It doesn’t make any sense –because people aren’t gods: they just discover things, and they make mistakes, and their graduate students tell them why they’re wrong, and then they go on and do things better the next time. But there are no gods around. I mean, scientists do use the terms “Newtonianism” and “Darwinism,” but nobody thinks of those as doctrines that you’ve got to somehow be loyal to, and figure out what the Master thought, and what he would have said in this new circumstance and so on. That sort of thing is just completely alien to rational existence, it only shows up in irrational domains.

So Marxism, Freudianism: anyone of these things I think is an irrational cult. They’re theology, so they’re whatever you think of theology; I don’t think much of it. In fact, in my view that’s exactly the right analogy: notions like Marxism and Freudianism belong to the history of organized religion. So part of my problem is just its existence: it seems to me that even to discuss something like “Marxism” is already making a mistake. Like, we don’t discuss “Planckism.” Why not? Because it would be crazy. Planck [German physicist] had some things to say, and some of them are right, and those were absorbed into later science, and some of them are wrong, and they were improved on. It’s not that Planck wasn’t a great man-all kinds of great discoveries, very smart, mistakes, this and that. That’s really the way we ought to look at it, I think. As soon as you set up the idea of “Marxism” or “Freudianism” or something, you’ve already abandoned rationality.

It seems to me the question a rational person ought to ask is, what is there in Marx’s work that’s worth saving and modifying, and what is there that ought to be abandoned? Okay, then you look and you find things. I think Marx did some very interesting descriptive work on nineteenth century history. He was a very good journalist. When he describes the British in India, or the Paris Commune [70-day French workers’ revolution in 1871], or the parts of Capital that talk about industrial London, a lot of that is kind of interesting — I think later scholarship has improved it and changed it, but it’s quite interesting.5

He had an abstract model of capitalism which — I’m not sure how valuable it is, to tell you the truth. It was an abstract model, and like any abstract model, it’s not really intended to be descriptively accurate in detail, it’s intended to sort of pull out some crucial features and study those. And you have to ask in the case of an abstract model, how much of the complex reality does it really capture? That’s questionable in this case — first of all, it’s questionable how much of nineteenth-century capitalism it captured, and I think it’s even more questionable how much of late-twentieth-century capitalism it captures.

There are supposed to be laws [i.e. of history and economics]. I can’t understand them, that’s all I can say; it doesn’t seem to me that there are any laws that follow from it. Not that I know of any better laws, I just don’t think we know about “laws” in history.

There’s nothing about socialism in Marx, he wasn’t a socialist philosopher — there are about five sentences in Marx’s whole work that refer to socialism.6 He was a theorist of capitalism. I think he introduced some interesting concepts at least, which every sensible person ought to have mastered and employ, notions like class, and relations of production …

5. For Marx’s works that are mentioned in the text, see Karl Marx, “The Civil War in France” (1871)(on the Paris Commune); “On Imperialism in India” (1853)(on the British in India); Capital, Vol. I (1867)(on industrial London).

6. On the lack of discussion of socialism in Marx’s work, see for example, Daniel Bell, The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties, New York: Free Press, 1960, pp. 355-392 (“Two Roads from Marx”). An excerpt (pp. 368-369):

The paucity is extraordinary. In an address to the General Council of the International Workingman’s Association, published as The Civil War in France, Marx said, at one point in passing, that communism would be a system under which “united cooperative societies are to regulate the national production under a common plan,” but nothing more. . . . In only one other place did Marx elaborate any remarks about the future society — the testy letter which came to be known as The Critique of the Gotha Programme. In 1875 the rival Lasallean and Eisenacher (Liebknecht, Bebel, Bernstein) factions met in Gotha to form the German Socialist Workers Party (Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands). As a political party, the socialists were confronted, for the first time, with the task of stating a political program on transition to socialism. Taking its cue from the [1871 Paris] Commune, the Gotha program emphasized two demands: the organization of producers’ co-operatives with state aid and equality.Marx’s criticism was savage. The demand for producers’ co-operatives, he said, smacked of the Catholic socialism of Buchez (the president of the Constitutional Assembly of 1848), while the demand for the “equitable distribution of the proceeds of labour” was simply a bourgeois right, since in any other society than pure communism the granting of equal shares to individuals with unequal needs would simply lead to renewed inequality. A transitional society, Marx said, could not be completely communal. In the co-operative society, based on collective ownership, “the producers do not interchange their products.” There would still be need for a state machinery, since certain social needs would have to be met. The central directing agency would make deductions from the social product: for administrative costs, schools, health services, and the like. Only under communism would the State, as a government over persons, be replaced by an “administration of things. . . .” [D]espite his theoretical criticisms of the transitional program, there is little in the Critique of a concrete nature regarding the mechanics of socialist economics either in the transitional or the pure communist society.

Richard Wolff keeps repeating that in trying to assess the merits of some claim, it is wise to listen to the proponents and the opponents of the claim. His interest is in the evaluation of capitalism. However, he does not tell us who he thinks is the best proponent of capitalism, but he does tell us that a formidable opponent of capitalism was Karl Marx.

Well, I am not ready to become a Marx scholar — there is too much to read. I want some trustworthy intellectual to tell me in a succinct formulation what I should learn from Marx. Who should I listen to?

And the above reasoning applies to all claims. The problem is this. It is living people who are writing and speaking on popular media and making an impact. And this is what creates something like “current popular opinions.” Couple this with a belief that the new is better than the old — a sort of belief in the inevitability of progress — and the “old” is placed in the dustbin of the antiquated.

It is true that the natural sciences and technologies advance, but this does not seem to be true of the moral and social studies where there is ongoing controversy.

To deal with this problem, I have sought to find intellectuals who have an aura of wisdom and authority. In the past — until the scientific revolution — Plato and Aristotle played such a role. They acted as a “benchmark” for evaluating claims. A few years ago I advocated treating the views of the British philosopher C. D. Broad for this role of a “benchmark,” giving the name “default philosopher” to such a role.

This is not to deprive other philosophers of a high status, but the fact remains that someone who lives later and can critically evaluate the scholarship of the past — has an advantage, provided he has done so well.

For topics not dealth with by C. D. Broad, I would extend the status of a default philosopher to Bertrand Russell.

As to present global affairs — involving war, economics, and politics — the current “default intellectual” — if I may use this phrase — is, for me: Noam Chomsky.

What is the practical implication of this view? One should read Chomsky, and when listening or reading where a claim is made about present global affairs, ask yourself: What is Noam Chomsky view on this?

Well, there is someone out there on the internet who is using the views of Noam Chomsky as the benchmark to compare the views of currently fashionable people — what can I call them? — celebrities?. This critical assessor is someone who calls himself — using Quine’s famous term — Dr. Gavagai.

Here are some of his videos — juxtaposing the views of Jordan Peterson with those of Noam Chomsky.

Here is a juxtaposition of Chomsky and Slavoj Zizek. I must confess that I have a systematic hard time understanding Zizek. Anyway, his only objection to Chomsky seems to be the claim — correct or not — that in the case of the Khmer Rouge, he underestimated the extent of their genocide.

Marx and Engels wrote a lot, and on all sorts of topics. What they had to say about science, metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, etc., may be interesting, but, to me, none of this is Marxism. Marxism, to me, is a definition and analysis of what Marx understands as “capitalism.” Moreover, it is not a characterization of capitalism under government control, but an analysis of “laissez faire capitalism” or what currently goes by the name of “anarcho-capitalism.” Capitalism is the market system composed of two classes — the bourgeoisie (his name for entrepreneurs and business owners) and the proletariat (workers or people who do not have access to subsistence other than selling their labor services). There are in some countries and regions of the world people who are neither bourgeois-es nor proletarians (i.e., people who do not live under capitalism). These are indigenous people and free peasants. By a “free peasant” I mean one who is not renting, who does not have a mortgage, and does not pay taxes. Are there such people? James Scott wrote a study of such people (look here)

What does Marxism say about these people? Nothing. Why? Because they are not part of the capitalist economy, and Marxism is an analysis of the capitalist economy. And what does Marx say about the capitalist economy? That it has the seeds of its own destruction. And that is all that Marxism means to me. Mind you, what Marx wrote about was a model of pure capitalism, i.e., anarcho-capitalism, as we may call it today. He was not writing about capitalism with government intervention (i.e., the welfare state or crony capitalism).

Marx anticipated a classless state which he called communism. But such anticipations or predictions are not essential to the claim that pure capitalism will self-destruct. This prognosis is the “scientific” socialism of Marxism, as contrasted with a moral ideal of a classless society espoused by so-called “utopian” or libertarian socialists.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, people seized land from large estates — creating a country of relatively free peasants. What would Marx say about such peasants? I suppose he would congratulate them for their freedom; and if they organized themselves by regional councils — still more congratulations. [See the Marx-Zasulich Correspondence (1881)]

Now what did the Bolsheviks in Russia, who called themselves “Marxists” do? Under Stalin, they liquidated the peasants in Ukraine by the millions. I ask: by what diabolical train of reasoning can you get such a policy from Marx?

I am still trying to recover from Jordan Peterson’s condemnation of Marxism because of what Stalin did.

Jordan Peterson by rejecting Marxism, contextually implied that he knows what Marxism is. But he can’t because the term “Marxism” is ambiguous and vague. If we try to clarify, here are some of the issues which will face us.

Someone may say that Marxism is the view of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Such a claim would assume that their views were if not identical, at least so close as to be equivalent. Now, to determine whether this is so, requires doing scholarship — reading all of the writings of Marx and Engels. Someone who does such a thing may be called a Marx and Engels scholar, and this does not make them Marxists unless they also agree with what they read.

Now, in reading any text, there is an element of interpretation. And if there is any inconsistency in the texts, the interpretation, in order to restore consistency, must take a stand. I suppose a systematization of the writings of Marx and Engels will be akin to something akin to a systematized theology. But formulating a coherent system — even if one agrees with it — will not be Marxism, unless some of the claims are peculiar only

to Marx, and are adhered to.

In short, there are as many “Marxisms” as there are interpretations of Marx. Furthermore there may be some who, like Humpty Dumpty, call themselves “Marxists” (like Stalin) by sheer prescription or fiat.

George Carlin, in one of his skits [see below], concluded with “fuck hope,” and went on to explain: “And please don’t confuse my point of view with cynicism -– the real cynics are the ones who tell you everything’s gonna be all right.”

Although Carlin was careful and precise about the use of language, I think he was wrong about cynicism.

Cynicism is in the ball park of pessimism and skepticism, so we must distinguish them. A skeptic is someone who expresses doubt about the truth of some claim. Let us say the claim is that everything will be all right. His attitude is one of uncertainty one way or the other; whereas the optimist is confident that everything will be all right, and the pessimist is equally confident that it will not. So, where does the cynic fit in?

It has to do with what one believes about human nature. There is a position believed by some called “psychological egoism.” This is the position that humans, by nature, are selfish and do everything with their personal interest in mind. If this position is correct, then so-called altruistic actions are only apparently so. If now everything turning out all right depends on genuinely altruistic actions, then the cynic denied this possibility, and therefore is a convinced pessimist.

We must, in view of this, view the normal pessimist and optimist as both subscribing to the view that genuine altruistic actions are possible; with the pessimist saying that they are not probable in the situation; whereas the optimist saying that they are probable. And the cynic saying that real altruistic actions will not occur — not because they are improbable, but because they are impossible.

If the cynic then tells you that things will be all right, he is speaking ironically or sarcastically. So, what Carlin is calling a real cynic, is an ironic or a sarcastic cynic.

George Carlin was both ironic and sarcastic at times, but he was never an ironic or sarcastic cynic. He did not believe that human doom was inevitable, only that it was probable.